COT review of BPA

In this guide

In this guideOn this page

Skip the menu of subheadings on this page.This is a background paper for discussion. It has not been finalised and should not be cited.

29. Following the publication and assessment of the new EFSA Opinion in 2023, the COT agreed that while the TDI would need to be revised to account for new evidence, the WoE did not support the conclusions drawn by EFSA or a TDI as low as that derived by EFSA. In line with the EMA and BfR, the COT raised a number of concerns, highlighting there was a lack of transparency on how the evidence had been integrated by EFSA to derive the POD for the derivation of a HBGV. EFSA also utilized a predetermined protocol which restricted the inclusion of studies and subsequent data evaluation to a specific time period. The COT acknowledged that given the size of the database, undertaking a risk assessment on BPA, with a WoE approach and transparent data integration, would not be a short undertaking. However, there was a wider data set available for BPA, which should have been considered by EFSA, not only in the evaluation for the relevant endpoint selection but also in the derivation of the HEDF.

30. To ensure timely assurance of consumer protection in the UK, the COT considered the WoE assessment by EFSA (2015, 2023) and the BfR (2023), as well as their methodological approach to derive a HBGV. To ensure no relevant evidence had been published since the BfR’s assessment, a literature search was undertaken, focussing on any new publications between January 2022 and June 2024, using an in-house search engine and retrieving publications from PubMed, Scopus, Ebsco (Food Science Source) and Springer (see Annex A for search terms). In line with EFSA (2015; 2023) and the BfR (2023), the COT concluded that other toxicological endpoints were consistently seen at higher dose ranges than those which resulted in immunological or reproductive effects, hence any HBGV based on either of these two endpoints would also be protective for other toxicological endpoints. The literature search therefore focused on the main endpoints of BPA, i.e. reproductive and immunotoxicity, but also included search strings for pathology and histopathology. Articles were excluded if they were general review articles, focused on other effects, were published prior to 2022 or focussed on biomonitoring (occurrence data) or detection methods of BPA.

31. While the COT acknowledged the diverging opinion by the EMA it was not further considered in the COT’s assessment of BPA. The EMA raised scientific issues with the endpoint applied by EFSA for the derivation of a HBGV, which align with the concerns highlighted by the COT, however the EMAs approach to risk assessment differs from that of the COT, insofar that it also considers the risk against the benefit.

32. The COT also considered assessments undertaken by other European or international authorities. While the Committee considered it useful to have seen the RIVM’s assessment, specifically the second part, they noted that the report was published in 2016 and therefore did not address either the selection of the critical endpoint nor the approach taken by EFSA in 2023. As the report was published prior to the EFSA 2023 assessment it would have fed into the new EFSA opinion but would also be unable to provide answers to the concerns raised by the COT. The US FDA published a technical review in 2024 based on four studies, all of which the COT noted were also discussed as part of the BfR assessment. The COT considered the technical review clear and scientifically robust but due to differences in weighing of evidence, the US FDA reached a different conclusion on these studies, confirming their previous position on BPA and seeing no need to change their current advice.

33. The COT acknowledged the list of alternatives provided by the RIVM, as well as any other considerations given to alternatives in the EU. However, assessing alternatives was outside the mandate of the COT.

Immune effects

34. EFSA considered the increase in Th17 cells, cells involved in immune responses, the most sensitive endpoint and hence the critical effect for BPA exposure.

35. Looking at the body of evidence, the COT acknowledged that there was clear evidence for BPA causing inflammation and an increase of Th17 cells. Exposure of mice and their offspring to BPA resulted in increased interferon gamma (IFN-ɣ) (colon, lamina propria, mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN)), Th1 cells (spleen) and Th17 cells (lamina propria, MLN, spleen) and a decrease in lysosome activity (intestine), immunoglobulin A (IgA) concentration (faecal samples), IgA plasma cells (lamina propria), IgA cells (colon), activated T cells (lamina propria), Th cells (MLN), Treg cells (lamina propria, spleen) MLN dendritic cells and increases in interleukin-17 (IL-17), IL-21, IL-6 and IL-23 in the serum. In addition, changes in anti-ovalbumin (anti-OVA) IgE in serum were reported as well as changes in IL-4, IL-13, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IFN-ɣ in splenocytes, percentage of macrophages and lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophiles and the up- or downregulation of genes associated with inflammation (Bodin et al., 2014; O’Brian et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2016; Malaise et al., 2018; Ye et al., 2023; Gu et al., 2024).

36. A study by Dong et al. (2023) suggested that exposure to BPA contributed to the development of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). However, it is important to note that this study, as well as several other studies looking at BPA exposure and inflammatory responses, used susceptible (animal) models for inflammation. This raised the question whether the development of SLE in the susceptible mice strain (MRL/lpr), or reduced lung function in murine asthma models could be considered true apical endpoints. The transferability of these results to humans was further unclear, disease models in mice not being representative of the human situation. In addition, not all studies assessing immunological endpoints were conducted to OECD guidelines or good laboratory practice (GLP) standards. Hence, The COT considered, that while these studies added to the overall body of evidence, they had a number of limitations, and it was unclear whether they demonstrated a true effect of BPA.

37. Th17 cells are well established as an indicator/marker for inflammation, however, because inflammation is driven by numerous factors, it is unclear what an apical endpoint based on changes in Th17 cells would represent. To date there have been no studies available showing the progression from such an intermediate endpoint, i.e. an increase of Th17 cells, to an apical effect, i.e. an inflammatory response/effect, at a concentration of BPA relevant to human exposure. In addition, no data have been available demonstrating a clear linkage or adverse outcome pathway (AOP) of BPA exposure to an adverse immunological endpoint.

38. In general, the COT queried whether an intermediate endpoint would be sufficiently robust to derive a HBGV, but they specifically did not agree with EFSA that an increase in percentage of Th17 cells was a scientifically relevant and robust intermediate endpoint to be utilised in the derivation of a new HBGV for BPA. After weighing the available data, the COT concluded that appropriate evidence was lacking that the change in Th17 cells consistently led to adverse immune effects or inflammatory response in humans. Therefore, immunological effects were not scientifically justifiable to predict adverse health effects of BPA. Given the uncertainties over the endpoint, a more robust WoE approach and evidence integration should be applied to a wider dataset to derive a more reliable and relevant endpoint on which to base the HBGV.

Reproductive effects

39. In 2015, based on the available evidence, EFSA concluded that BPA caused adverse effects on reproduction. However, those effects were only seen in experimental animals, with high variability; effect doses varied from 100 - 450,000 µg/kg bw per day. In 2023, based on the evidence assessed, EFSA concluded once more that BPA adversely affected development and male and female reproduction in experimental animals, i.e. an adverse effect was “likely”. In line with their previous assessment, however, EFSA considered the available human data not sufficient to establish a causal relationship between BPA exposure and developmental and/or reproductive effects in humans.

40. In 2023, the BfR acknowledged that the variability in the data, including new evidence, continued to be considerable, however they nonetheless deemed the scientific evidence sufficient to consider effects on male reproduction the key adverse effect of BPA. This was based on a WoE approach, focussing on the most likely endpoints, as identified by EFSA (2023), i.e. sperm motility, testis and epididymis histology.

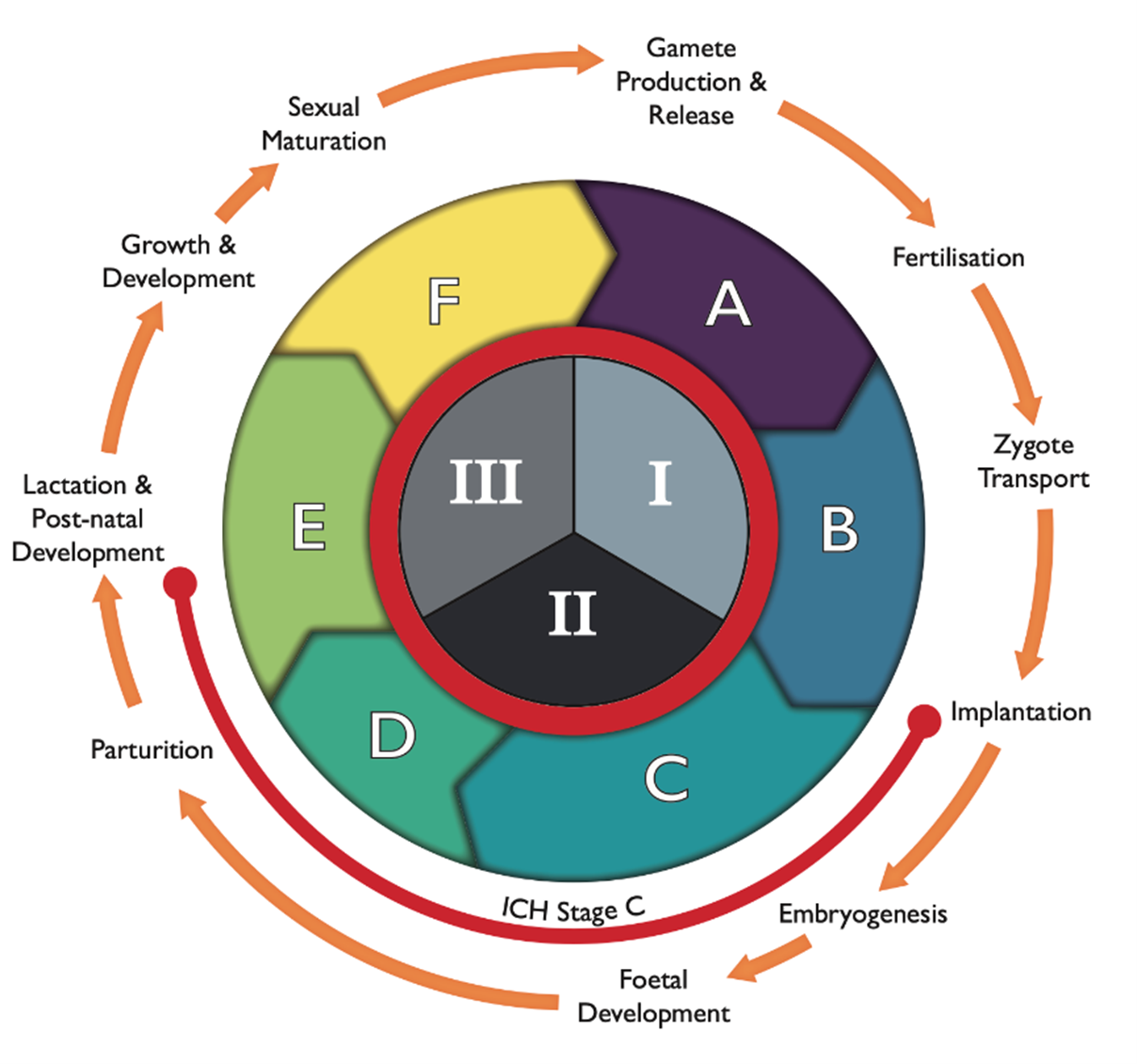

41. The COT critically appraised both EFSA’s and the BfR’s WoE approach and subsequently agreed with the BfR's selection of the key endpoint, i.e. male reproduction. However, to ensure all relevant information had been evaluated, the COT also considered evidence on reproduction published since the BfR’s assessment. The new evidence was thereby categorised using the three stages of the developmental and reproductive cycle and separated into studies of male and female biology to ensure the appropriate endpoints were reviewed in line with the WoE approached used by the BfR (Figure 1).

42. The new studies (70) on reproductive endpoints were predominantly mechanistic and/or in vitro studies. While these were supportive in providing information on the mode of action (MoA) at relatively consistent dose ranges, they did not provide any new knowledge on the MoA of BPA on reproductive effects.

43. While several of the in vivo studies focussed on interventions to ameliorate effects of BPA with various substances (including natural products), the studies by Molangiri et al. (2022) and Sturm et al. (2022) assessed male reproductive endpoints after pregnancy exposure with low concentrations of BPA, 0.4 - 40 µg/kg bw per day and 25 µg/kg bw, respectively. Molangiri et al. (2022) reported effects on male reproduction, including high plasma testosterone, thickened membranes in the testis and reduced sperm motility via impaired phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-protein kinase B (PI3K-AKT) signalling and increased testicular gene (TEX11) expression. While the MoA for BPA was different, the study suggested a window of susceptibility in utero that could have long lasting effects on male reproduction. In contrast, the study by Sturm et al. (2022) did not report any reproductive effects. While there was some change in testicular tissues, i.e. lower epithelial height of seminiferous tubules, this change did not have an impact on the apical endpoint. However, as the study was undertaken at low concentration, it added to the database around the lowest observed adverse effect level (LOAEL) and NOAEL of BPA.

44. Recent epidemiological studies were limited. Two biomonitoring studies provided further evidence of human exposure to BPA and potential risks to the population, however data on reproductive or fertility endpoints were lacking (Hwang et al., 2023; Holmboe et al., 2022). A cross-sectional study by Jeseta et al. (2024) in 385 males (17 - 62 years of age; 2019 - 2021) provided a good assessment of BPA in male semen samples. The results showed no significant correlation between traditional markers of sperm health and BPA, such as sperm concentration, volume and total sperm count, and integrity of spermatozoa deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), however, the data did show significant correlation between the concentration of BPA and decreased sperm motility and altered morphology.

45. Recent experimental data on the adverse effects of BPA on the female reproductive system reported effects on oocyte and ovarian weight as well as changes to reproductive hormones, ovarian follicles and ovarian development (Ozkemahli et al., 2022; Gonzalez-Gomez et al., 2023; Teteau et al., 2023). No evidence of causation could be established in a recent correlation study by Zhang et al. (2023) assessing BPA exposure and ovarian function and oocyte reserve in 111 women from a fertility clinic in North China from 2020 - 2021.

46. Generally, effects on the female reproductive system were seen at doses several magnitudes higher than the POD used by both EFSA and the BfR. Hence, effects on the female reproductive system have not been further considered by the COT and the Committee agreed with the BfR that a HBGV derived based on male reproductive effects would also be protective for effects on the female reproductive system.

47. Weighing all available evidence, the COT agreed with the BfR’s assessment that the adverse effect of BPA on male reproduction was the critical endpoint and should be carried forward for the derivation of a HBGV. Data published since the BfR’s assessment, while informative and adding to the overall database of BPA, did not provide any information to change the COTs current view.

Other toxicological endpoints

48. In 2023, EFSA followed a predefined protocol to derive available evidence since their 2015 evaluations; this included the evaluation of some evidence not considered in their earlier assessment (EFSA,2015). In addition to immunotoxicity and reproductive toxicity, EFSA also considered carcinogenicity, genotoxicity, hepatotoxicity and renal toxicity, cardiotoxicity, neurotoxicity and developmental neurotoxicity, developmental and reproductive toxicity, as well as effects on body weight, the lung, thyroid, parathyroid, pituitary and adrenal glands, the mammary gland, bone marrow, and haematological and metabolic effects.

49. The BfR conducted a targeted systematic literature review retrieving evidence from 2013, using the 2015 EFSA opinion as a starting point, on the reproductive and immunotoxic effects of BPA. While the review also considered metabolic effects, the available studies on increased serum uric acid were not considered suitable for a quantitative hazard assessment. The BfR however noted that there remained uncertainty over this endpoint and more data would be required. Other endpoints, e.g. effects on the liver or kidney were not included in the review as EFSA (2015; 2023) and ECHA (2014) had consistently reported the absence of adverse effects in the dose range of interest (≤ 4 µg/kg bw per day for humans). The BfR agreed with this conclusion, as well as EFSA’s conclusion that it is “unlikely to very unlikely” that BPA presented a genotoxic hazard or demonstrated tumorigenic activity. The BfR did however include and consider any new information on the toxicokinetics of BPA, due to their criticism of the factor EFSA used for the extrapolation from the critical dose in rodents to humans.

50. The COT agreed with EFSA and the BfR that BPA did not demonstrate genotoxic or carcinogenic potential and that adverse effects other than immunotoxicity or reproductive effects occurred at higher concentrations and were therefore not of direct relevance. Therefore, the in-house literature search (non-systematic) conducted by the COT in 2024 focussed on any new publications on the potential immunotoxic or reproductive effects of BPA since the publication of the BfR assessment. However, for completeness a literature search for pathology/histopathology was also included. Although the search terms were quite narrow a number of papers were retrieved which covered BPA more broadly or considered the general toxicity of BPA.

51. Two of the papers retrieved did not include primary data. Prueitte and Goodmann (2024) was a critique of the EFSA assessment, and their use of an intermediate immunotoxicity endpoint, which had not been observed in species other than mice. The authors concluded that EFSA’s new TDI was not supported by the totality of the available database on BPA but indicated that the t-TDI established by EFSA in 2015 would continue to be protective of human health. Kortenkamp et al. (2022) conducted a systematic review of BPA exposure and decline in semen quality. The authors were critical of both the EFSA and BfR assessment, stating that neither authority assessed the evidence on reproductive effects accurately. The COT noted that the review by Kortenkamp et al. (2022) focussed on reproductive endpoints only and did not include considerations on immunotoxicity or the wider potential effects of BPA. The COT reviewed the information within the paper and highlighted that the papers cited by Kortenkamp et al. (2022) to underpin their interpretation of the evidence would have been available to EFSA and the BfR at the time.

52. The COT concluded that the new evidence on general toxicity, pathology/histopathology or evidence included in the reviews/critiques highlighted above was not sufficient to alter the Committee’s current alignment with the BfR.

Considerations on the point of departure

53. EFSA (2023) derived a BMDL40 of 0.53 µg/kg bw per day based on the study by Luo et al. (2016), which exposed pregnant mice to BPA concentrations equivalent to 0.475, 4.75 and 47.5 µg/kg bw/day, as a POD for their derivation of a HBGV. The BfR (2023) derived a BMDL10 of 26 µg/kg bw per day based on a dose range of 2- 200 µg/kg bw per day (Liu et al., 2013) and a NOAEL of 50 µg/kg bw per day based on a dose range of 50-1000 µg/kg bw per day as their POD.

54. Apart from the studies by Molangiri et al. (2022) and Darmani and Alkhatib (2024) the dose ranges or PODs in the studies identified in the recent literature search were orders of magnitude higher than the PODs used by EFSA and the BfR. Molangiri et al. (2022) exposed rats to a concentration of BPA of 0.4 µg/kg bw per day, which was lower than the BMDL derived by EFSA, albeit not by much, but approximately 100-fold lower than the POD applied by the BfR. The authors reported significant effects such as an increased weight in offspring, a significant reduction in the expression of estrogen-related receptor gamma (ERRɣ) and changes in gene expression. Testicular morphology showed changes such as disoriented arrangement of seminiferous tubules, irregular-shaped Leydig cells, and a smaller number of mature sperms in lumens. Darmani and Alkhatib (2024) reported changes to serum hormone levels at a concentration of 10 µg/kg bw per day after exposure to BPA dimethacrylate (DMA). This is approximately a quarter of the NOAEL established by the BfR for BPA but still 20-fold higher than the POD applied by EFSA.

55. Although the effects reported in the study by Darmani and Alkhatib (2024) were at a concentration lower than the POD established by the BfR, they were based on BPA-DMA, rather than BPA itself. Hence, while these provide an indication of adverse effects, it is not clear whether the effects seen with BPA-DMA are consistent with effects of BPA seen at the same concentration. The effect dose was still higher than the POD applied by EFSA. While results by Molangiri et al. (2022) were in line with previous studies, demonstrating adverse effects on male offspring after in utero exposure, albeit at lower levels, the focus of the study was predominantly on BPS. Additional data would be required to fully establish whether the reported effects could be consistently seen at the reported dose levels.

56. While both studies contributed to the overall knowledgebase, the COT did not consider the evidence sufficient to reconsider their current alignment with the BfR or that the TDI would not be sufficiently protective of adverse effects of BPA.

Derivation of the TDI

57. Both EFSA and the BfR acknowledged that the interpretation of the available evidence and divergence in the risk assessment were linked to the tools and methodologies applied. The key points of divergence were the adverse effect definition, the inclusion/exclusion of scientific information, the use of an apical versus intermediate endpoint, uncertainty analysis and HEDF.

58. To derive the POD for the derivation of the HBGV the BfR undertook BMD modelling on all relevant studies. While the effects on male reproduction were considered the critical endpoint, immunotoxicological studies were also submitted to BMD modelling to evaluate to which extent the HBGV would also be protective for immunological effects. Weighing all evidence, the BfR based their derivation of the TDI on the effect dose for reduced sperm count in two sub-chronic studies in rats (Liu et al., 2013; Srivastava and Gupta, 2018). Studies where the NOAEL was the highest dose tested were excluded from further assessment as it was unclear at which dose, if any, a BMR would have been reached. The two selected studies were submitted to a probabilistic uncertainty assessment according to the approach by the World Health Organisation (WHO IPCS, 2017). Differently to EFSA’s deterministic approach, the distribution of possible HEDs resulting from toxicokinetic data were thereby combined with typical distributions for other uncertainties.

59. Both EFSA and the BfR extrapolated the reference point (RP) to the TDI by substituting the toxicokinetic standard subfactor for interspecies extrapolation by a BPA-specific HEDF. The COT noted that both authorities applied the same human data, however the animal studies they used differed. This difference in animal studies resulted in HED values differing by two orders of magnitude, which in turn, together with the different approaches to the derivation of the TDI (deterministic versus probabilistic), led to the difference in magnitude for the resulting HBGV. The approach taken by the BfR comprised a significant degree of conservatism in the derivation of the TDI, however, the COT deemed the overall assessment to have avoided unnecessary conservatism.

60. While the COT acknowledged that there was clear evidence of BPA causing an effect on the immune system, the evidence as a whole was not strong enough to support immunotoxicity as the critical endpoint. However, the TDI derived by the BfR would still be protective of a significant increase in the respective intermediate endpoint, as well as protective with respect to other toxicological endpoints. Based on the current body of evidence, adverse immunological effects in humans, or other toxicological effects were unlikely to result from exposures in the range of the TDI of 0.2 μg/kg bw per day and would require higher exposure concentrations.

Considerations on the exposures of UK consumers

61. In line with EFSA and the BfR, the COT highlighted that the most recent exposure data predated the 2015 EFSA opinion. A comparison of the t-TDI with exposure estimates in 2015 found no health concern for any age group from dietary exposure and low health concern (i.e. considered unlikely to cause adverse health effects) from aggregate exposure to BPA. While EFSA was not explicitly asked to perform an exposure assessment in their 2023 evaluation, using the exposures estimated from 2015 would lead to exceedances of approximately 2-3 orders of magnitude. However, EFSA noted that the data used in their 2023 evaluation may not accurately reflect the current exposure scenarios of consumers. Both, the BfR and the COT agreed with the uncertainties in this approach. The BfR did not undertake an exposure assessment in their evaluation and both the BfR and the COT stressed the importance of updated occurrence levels to fully assess any potential risks to consumers.

62. While adopting the TDI set by the BfR was a precautionary approach, the COT highlighted that having an up-to-date exposure assessment would further mitigate any potential risk as it would provide an up to date picture of the current UK exposures and provide evidence compared to EFSA’s more stringent approach.