TOX/2025/47 Annex A

Introduction

In this guide

In this guideThis is a background paper for discussion. It has not been finalised and should not be cited.

1. Bisphenol A (BPA) is used as a monomer in the manufacture of polycarbonates (PC), epoxy resins and other polymeric materials, and certain paper products (thermal printing). BPA has been prohibited in coatings and varnishes for food contact materials (FCMs) intended for infants and young children since 2018. However, it continued to be used and authorised in the European Union (EU) and United Kingdom (UK) for applications such as reusable bottles, tableware and storage containers, thermal paper coatings and protective linings of food and beverage cans and vats. Where BPA was permitted at the time, operators had to ensure that BPA observed the specific migration limit (SML) of 0.05 mg/kg (EFSA, 2021). The SML set in the EU and UK was based on the European Food Safety Authority’s (EFSA) 2015 evaluation of BPA and a Temporary Tolerable Daily Intake (t-TDI) of 4 µg/kg body weight (bw) per day.

2. Following a mandate from the European Commission (EC) in 2016 to re-evaluate the risk to public health related to the presence of BPA in foodstuffs, EFSA established a new TDI of 0.2 ng BPA/kg bw per day in their final evaluation in 2023. Although this final TDI was higher than the initially proposed level, mean and high level consumers of all age groups would exceed the new TDI by 2-3 orders of magnitude.

3. In December 2024, the EU adopted a ban on the use of BPA in FCMs, which took effect in January 2025, with an 18-month phase-out period for industry compliance. The ban means that BPA will no longer be allowed in products that come into contact with food or drink, e.g. coating of metal cans, reusable plastic bottles, water coolers and other kitchenware. The EU ban also included BPA’s salts and other bisphenols and bisphenol derivatives, as a precautionary principle, due to shared characteristics with BPA, such as similarities in structure and activity (EC (No) 2024/3190). Some bisphenols, e.g. bisphenol S (BPS), have already been subject to harmonised classification and have been listed in Part 3 of Annex VI Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 as they have demonstrated hazardous properties to human health, i.e. reproductive toxicity.

Evaluations prior to the 2023 EFSA Opinion

In this guide

In this guideThis is a background paper for discussion. It has not been finalised and should not be cited.

EFSA

4. In 2015, EFSA assessed the risk to public health from exposure to BPA using a weight of evidence (WoE) approach and considered reproductive and developmental effects, neurological and neurodevelopmental effects, immune effects and cardiovascular and metabolic effects “as likely as not” but considered it “unlikely” for BPA to be carcinogenic or mutagenic. Adverse effects on the kidney and mammary gland were considered “likely” and subject to benchmark dose (BMD) modelling. EFSA calculated a lower confidence level of the BMD (BMDL10) of 8,960 µg/kg bw per day for changes in mean relative kidney weight in a two-generation toxicity study in mice, however no BMDL10 could be calculated for mammary gland effects. Based on the available data on toxicokinetics, the BMDL10 was then converted to a human equivalent dose (HED) of 609 µg/kg bw per day. EFSA applied a total uncertainty factor (UF) of 150 (2.5 for interspecies differences (2.5 for toxicodynamics and 1 for toxicokinetics as toxicokinetic differences have been addressed in the HED approach),10 for intraspecies differences, and an extra factor of 6 to account for the uncertainties in the database; 2.5 x 10 x 6) to the HED to derive a t-TDI of 4 µg/kg bw per day.

5. Based on estimated exposures, EFSA concluded there was no health concern for any age group from dietary exposure to BPA and a low health concern from aggregated exposure, i.e. exposure to BPA from all sources. EFSA however noted there was considerable uncertainty in the exposure estimates for non-dietary sources.

Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM)

6. In 2014, the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) published a report, providing an overview of the current state of knowledge on BPA (Part 1).

7. In 2016, the RIVM published recommendations for risk management (Part 2) evaluating the scientific knowledge and assessing possible health risks. The RIVM concluded that based on the current health hazard and information on exposure there was no health concern for BPA at the levels of dietary exposure estimated by EFSA in 2015 and low concern on aggregate exposure. A risk among neonates in intensive care units and foetuses of pregnant workers through dermal exposure could not be excluded. In addition, a risk among general workers involved with BPA manufacture as well as skin sensitisation of workers in industry processes working with BPA could not be excluded.

8. The RIVM also considered immunological data published by Menard et al. (2014a, b) which suggested that BPA could lead to the development of food allergies and have adverse effects on resistance to infections at exposures lower than the current European standards, i.e. the occupational exposure limit (OEL), t-TDI and dermal derived no effect level (DNEL). Neonates, infants and young children appeared to be more susceptible. Following the same approach as EFSA in 2015 to derive a t-TDI, the RIVM highlighted that the effects were observed in animals at a HED potentially a factor of 10 lower than the HED on which EFSA based its t-TDI on. The RIVM therefore concluded that the new study warranted reconsideration of the current standards and recommended that the Dutch Government file a request to EFSA to revisit the t-TDI, to the EC to revisit the occupational exposure limit (OEL) and the derived no effect levels (DNELs) and to the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) to re-open the evaluation of the health hazard of BPA.

9. The RIVM considered that the risk may be reduced through substitution of BPA with alternatives and included a number of alternatives in its report. They did however acknowledge that for most of these alternatives, toxicological characterisation was lacking.

Opinion of the EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials, Enzymes and Processing Aids (CEP), 2023

10. In 2016, the EC mandated EFSA to re-evaluate the risk to public health related to the presence of BPA in foodstuffs and establish a TDI. For the derivation of their new TDI, the EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials, Enzymes and Processing Aids (CEP) assessed the evidence from animal data and human observational studies, following a pre-established protocol, and any new evidence since their last evaluation in 2015.

11. EFSA identified the immune system as the most sensitive target of BPA based on an increase in the percentage of Th17 cells reported in female mice treated with BPA via drinking water from gestational day (GD) 0 to postnatal day (PND) 21. Th17 cells are a subset of pro-inflammatory T helper cells which play a pivotal role in immune responses and are involved in inflammatory conditions. While EFSA agreed that no direct causal link between the observed increase in Th17 cells and an inflammatory response has been established, they noted that there was evidence of a link between changes in the number of Th17 cells (an intermediate endpoint, i.e. not the final toxic effect) and adverse outcomes, as Th17 cells are involved in a number of diseases with inflammatory pathogenesis, e.g. psoriasis, asthma.

12. EFSA’s new TDI of 0.2 ng BPA/kg bw per day was based on a HED of 8.2 ng/kg bw per day, converted from the BMDL40 for a 40 % increase in the percentage of Th17 cells in mice. The benchmark response (BMR) was selected on the basis of the variance observed in the numbers of Th17 cells in a healthy human population. EFSA applied an overall UF of 50, using the default UFs of 2.5 and 10 for interspecies toxicodynamic differences and intraspecies variability in toxicokinetics and toxicodynamics, respectively. No UF was applied for interspecies variability in toxicokinetics as this was already accounted for in the conversion to the HED. EFSA did however apply an additional UF of 2 based on the uncertainty analysis performed. The resulting value was rounded to 0.2 ng/kg bw per day.

13. In their uncertainty assessment, EFSA applied a deterministic approach, deriving single point uncertainty estimates, combining multiple assumptions and applying them to the point of departure (POD) to derive the TDI.

14. While EFSA did not undertake an exposure assessment, given that the available exposure data were from 2008 – 2012, comparison of exposure estimates from 2015 would imply that mean and high level consumers of all age groups could potentially exceed the new TDI by 2-3 orders of magnitude.

Evaluations by Regulatory bodies since the EFSA 2023 Opinion

In this guide

In this guideThis is a background paper for discussion. It has not been finalised and should not be cited.

15. During the public consultation on the new EFSA opinion in 2021/2022, both, the European Medical Agency (EMA) and the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) provided comments to EFSA, highlighting their diverging views from EFSA, i.e., on the use of an intermediate endpoint for the derivation of a health based guidance value (HBGV), the approach and timeframe applied for consideration of studies, and the risk assessment approach including the uncertainty analysis and clinical relevance/extrapolation from animals to humans and derivation of the HED.

16. As the diverging views could not be resolved, according to the founding regulation, EFSA (Article 30 of Regulation (EC) No 178/2002) and the EMA (Article 59 of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004) and BfR were obliged to present joint documents to the EC clarifying their scientific issues and identifying relevant uncertainties in the data. These documents are publicly available (EFSA/EMA, 2023; EFSA/BfR, 2023).

European Medical Agency (EMA)

17. The EMA did not agree with EFSA’s revised TDI due to the two agencies different scientific approaches to risk assessment and methodology for quantifying risk, i.e. the adverse effect definition, the intermediate versus apical endpoint (final observable), the approach applied for consideration of studies and the risk assessment approach including the clinical relevance/extrapolation from animal studies for use in humans.

18. EFSA and the EMA had diverging views on what could be considered sufficient scientific evidence to demonstrate that an intermediate endpoint in animals was causally associated with an adverse effect in humans. Furthermore, both agencies disagreed on the method for quantifying the risk and establishing an exposure level considered safe in humans.

German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR)

19. Both, EFSA and the BfR acknowledged that the interpretation of available information and risk assessment were linked to the tools and methodologies applied, resulting in their divergence of opinion. The key points of divergence were the adverse effect definition, the inclusion/exclusion of scientific information, apical versus intermediate endpoint (reference point acceptability, adversity, relevance), reproductive toxicity endpoints, uncertainty analysis and choice of HED factor (HEDF).

20. Due to their divergence with EFSA’s assessment, the BfR did not support the new TDI set by EFSA and published their own assessment of BPA in 2023. The assessment provided a re-evaluation of the critical endpoints identified by EFSA (2023) and an independently derived TDI.

21. The BfR undertook a literature review, and the reliability of the studies was assessed based on pre-defined criteria and grouped into three tiers reflecting the respective WoE. It should, however, be noted that the literature evaluation and assessment were limited to the critical endpoints identified by EFSA, i.e. reproductive toxicity, immunological effects, increased serum uric acid, and toxicokinetics. For their assessment, the BfR also considered the literature and data available on these endpoints from the EFSA 2015 and 2023 assessments.

22. The BfR considered the immunological studies to be inconsistent regarding effect size and dose response, as well as suffering from shortcomings in design and reporting. Given that the increase in Th17 cells represented only an intermediate endpoint, for which a causal link to apical effects in a dose range relevant to humans was unclear, the BfR considered immunological effects in humans, if they occurred, unlikely to result from BPA in the exposure range of the EFSA TDI. Hence, the BfR considered effects on the male reproductive system (i.e. decreased sperm count and motility, sperm viability, sperm morphology, changes to testis histology and weight) as the most sensitive endpoint and based its TDI derivation on reduced sperm count observed in two studies in rats (Liu et al., 2013; Srivastava and Gupta, 2018). Dose-response analysis performed on these two studies by BMD modelling resulted in a BMDL10 of 26 µg/kg bw per day for one study (Liu et al., 2013), and a no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) of 50 µg/kg bw per day for the other study (Srivastava and Gupta, 2018); data from the second study did not meet the BfR’s criteria for BMD modelling.

23. The BfR applied a probabilistic uncertainty approach (WHO IPCS/APROBA), using a range of probabilistic distributions, considering uncertainty in both directions, such that the value could be increased or decreased, thereby integrating the uncertainty analysis and derivation of the TDI. In contrast to EFSA, the BfR did not apply a single HEDF in the derivation of the TDI within the uncertainty analysis but applied the 5th and 95th percentile and median HED factors, together with typical uncertainties, e.g. interhuman variability, study duration.

24. Due to the conservatism in their assessment the BfR considered the resulting TDI of 0.2 µg/kg bw per day to be protective of 99 % of the population, with 95 % confidence. The TDI would also be protective for any other relevant effects/toxicological endpoints, including intermediate endpoints. Should BPA cause any adverse immunological effects in humans, the BfR considered it unlikely this would be at exposures in the range of the TDI.

United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

25. In 2024, following the publication of both EFSA’s and the BfR’s evaluations of BPA, the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) considered whether there was a need to change their position on the risk from BPA.

26. The US FDA assessed four studies in their evaluation, three were recent studies, and one had been previously evaluated. Of those four studies, two studies (Camacho et al., 2019; Dere et al., 2018) were negative for sperm effects, while the other two studies (Srivastava and Gupta, 2018; Liu et al., 2013, Part I and II) showed adverse effects on sperm parameters. The US FDA considered the negative studies methodologically strong with consistent findings, while the findings from the two positive studies were not easily comparable (FDA, 2024; unpublished).

27. Overall, the US FDA did not consider there to be any new evidence that would indicate an elevated concern regarding the effects of BPA on sperm parameters or testicular toxicity and therefore saw no need to change their previous conclusions on the safety of BPA. The US FDA therefore maintained a NOAEL of 5 mg/kg based on oral dosing studies for risk or safety assessments (FDA, 2014).

28. The US FDA noted that adverse effects occurred at concentrations of BPA that were well above established exposure levels in humans (FDA, 2024; unpublished).

COT review of BPA

In this guide

In this guideThis is a background paper for discussion. It has not been finalised and should not be cited.

29. Following the publication and assessment of the new EFSA Opinion in 2023, the COT agreed that while the TDI would need to be revised to account for new evidence, the WoE did not support the conclusions drawn by EFSA or a TDI as low as that derived by EFSA. In line with the EMA and BfR, the COT raised a number of concerns, highlighting there was a lack of transparency on how the evidence had been integrated by EFSA to derive the POD for the derivation of a HBGV. EFSA also utilized a predetermined protocol which restricted the inclusion of studies and subsequent data evaluation to a specific time period. The COT acknowledged that given the size of the database, undertaking a risk assessment on BPA, with a WoE approach and transparent data integration, would not be a short undertaking. However, there was a wider data set available for BPA, which should have been considered by EFSA, not only in the evaluation for the relevant endpoint selection but also in the derivation of the HEDF.

30. To ensure timely assurance of consumer protection in the UK, the COT considered the WoE assessment by EFSA (2015, 2023) and the BfR (2023), as well as their methodological approach to derive a HBGV. To ensure no relevant evidence had been published since the BfR’s assessment, a literature search was undertaken, focussing on any new publications between January 2022 and June 2024, using an in-house search engine and retrieving publications from PubMed, Scopus, Ebsco (Food Science Source) and Springer (see Annex A for search terms). In line with EFSA (2015; 2023) and the BfR (2023), the COT concluded that other toxicological endpoints were consistently seen at higher dose ranges than those which resulted in immunological or reproductive effects, hence any HBGV based on either of these two endpoints would also be protective for other toxicological endpoints. The literature search therefore focused on the main endpoints of BPA, i.e. reproductive and immunotoxicity, but also included search strings for pathology and histopathology. Articles were excluded if they were general review articles, focused on other effects, were published prior to 2022 or focussed on biomonitoring (occurrence data) or detection methods of BPA.

31. While the COT acknowledged the diverging opinion by the EMA it was not further considered in the COT’s assessment of BPA. The EMA raised scientific issues with the endpoint applied by EFSA for the derivation of a HBGV, which align with the concerns highlighted by the COT, however the EMAs approach to risk assessment differs from that of the COT, insofar that it also considers the risk against the benefit.

32. The COT also considered assessments undertaken by other European or international authorities. While the Committee considered it useful to have seen the RIVM’s assessment, specifically the second part, they noted that the report was published in 2016 and therefore did not address either the selection of the critical endpoint nor the approach taken by EFSA in 2023. As the report was published prior to the EFSA 2023 assessment it would have fed into the new EFSA opinion but would also be unable to provide answers to the concerns raised by the COT. The US FDA published a technical review in 2024 based on four studies, all of which the COT noted were also discussed as part of the BfR assessment. The COT considered the technical review clear and scientifically robust but due to differences in weighing of evidence, the US FDA reached a different conclusion on these studies, confirming their previous position on BPA and seeing no need to change their current advice.

33. The COT acknowledged the list of alternatives provided by the RIVM, as well as any other considerations given to alternatives in the EU. However, assessing alternatives was outside the mandate of the COT.

Immune effects

34. EFSA considered the increase in Th17 cells, cells involved in immune responses, the most sensitive endpoint and hence the critical effect for BPA exposure.

35. Looking at the body of evidence, the COT acknowledged that there was clear evidence for BPA causing inflammation and an increase of Th17 cells. Exposure of mice and their offspring to BPA resulted in increased interferon gamma (IFN-ɣ) (colon, lamina propria, mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN)), Th1 cells (spleen) and Th17 cells (lamina propria, MLN, spleen) and a decrease in lysosome activity (intestine), immunoglobulin A (IgA) concentration (faecal samples), IgA plasma cells (lamina propria), IgA cells (colon), activated T cells (lamina propria), Th cells (MLN), Treg cells (lamina propria, spleen) MLN dendritic cells and increases in interleukin-17 (IL-17), IL-21, IL-6 and IL-23 in the serum. In addition, changes in anti-ovalbumin (anti-OVA) IgE in serum were reported as well as changes in IL-4, IL-13, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IFN-ɣ in splenocytes, percentage of macrophages and lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophiles and the up- or downregulation of genes associated with inflammation (Bodin et al., 2014; O’Brian et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2016; Malaise et al., 2018; Ye et al., 2023; Gu et al., 2024).

36. A study by Dong et al. (2023) suggested that exposure to BPA contributed to the development of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). However, it is important to note that this study, as well as several other studies looking at BPA exposure and inflammatory responses, used susceptible (animal) models for inflammation. This raised the question whether the development of SLE in the susceptible mice strain (MRL/lpr), or reduced lung function in murine asthma models could be considered true apical endpoints. The transferability of these results to humans was further unclear, disease models in mice not being representative of the human situation. In addition, not all studies assessing immunological endpoints were conducted to OECD guidelines or good laboratory practice (GLP) standards. Hence, The COT considered, that while these studies added to the overall body of evidence, they had a number of limitations, and it was unclear whether they demonstrated a true effect of BPA.

37. Th17 cells are well established as an indicator/marker for inflammation, however, because inflammation is driven by numerous factors, it is unclear what an apical endpoint based on changes in Th17 cells would represent. To date there have been no studies available showing the progression from such an intermediate endpoint, i.e. an increase of Th17 cells, to an apical effect, i.e. an inflammatory response/effect, at a concentration of BPA relevant to human exposure. In addition, no data have been available demonstrating a clear linkage or adverse outcome pathway (AOP) of BPA exposure to an adverse immunological endpoint.

38. In general, the COT queried whether an intermediate endpoint would be sufficiently robust to derive a HBGV, but they specifically did not agree with EFSA that an increase in percentage of Th17 cells was a scientifically relevant and robust intermediate endpoint to be utilised in the derivation of a new HBGV for BPA. After weighing the available data, the COT concluded that appropriate evidence was lacking that the change in Th17 cells consistently led to adverse immune effects or inflammatory response in humans. Therefore, immunological effects were not scientifically justifiable to predict adverse health effects of BPA. Given the uncertainties over the endpoint, a more robust WoE approach and evidence integration should be applied to a wider dataset to derive a more reliable and relevant endpoint on which to base the HBGV.

Reproductive effects

39. In 2015, based on the available evidence, EFSA concluded that BPA caused adverse effects on reproduction. However, those effects were only seen in experimental animals, with high variability; effect doses varied from 100 - 450,000 µg/kg bw per day. In 2023, based on the evidence assessed, EFSA concluded once more that BPA adversely affected development and male and female reproduction in experimental animals, i.e. an adverse effect was “likely”. In line with their previous assessment, however, EFSA considered the available human data not sufficient to establish a causal relationship between BPA exposure and developmental and/or reproductive effects in humans.

40. In 2023, the BfR acknowledged that the variability in the data, including new evidence, continued to be considerable, however they nonetheless deemed the scientific evidence sufficient to consider effects on male reproduction the key adverse effect of BPA. This was based on a WoE approach, focussing on the most likely endpoints, as identified by EFSA (2023), i.e. sperm motility, testis and epididymis histology.

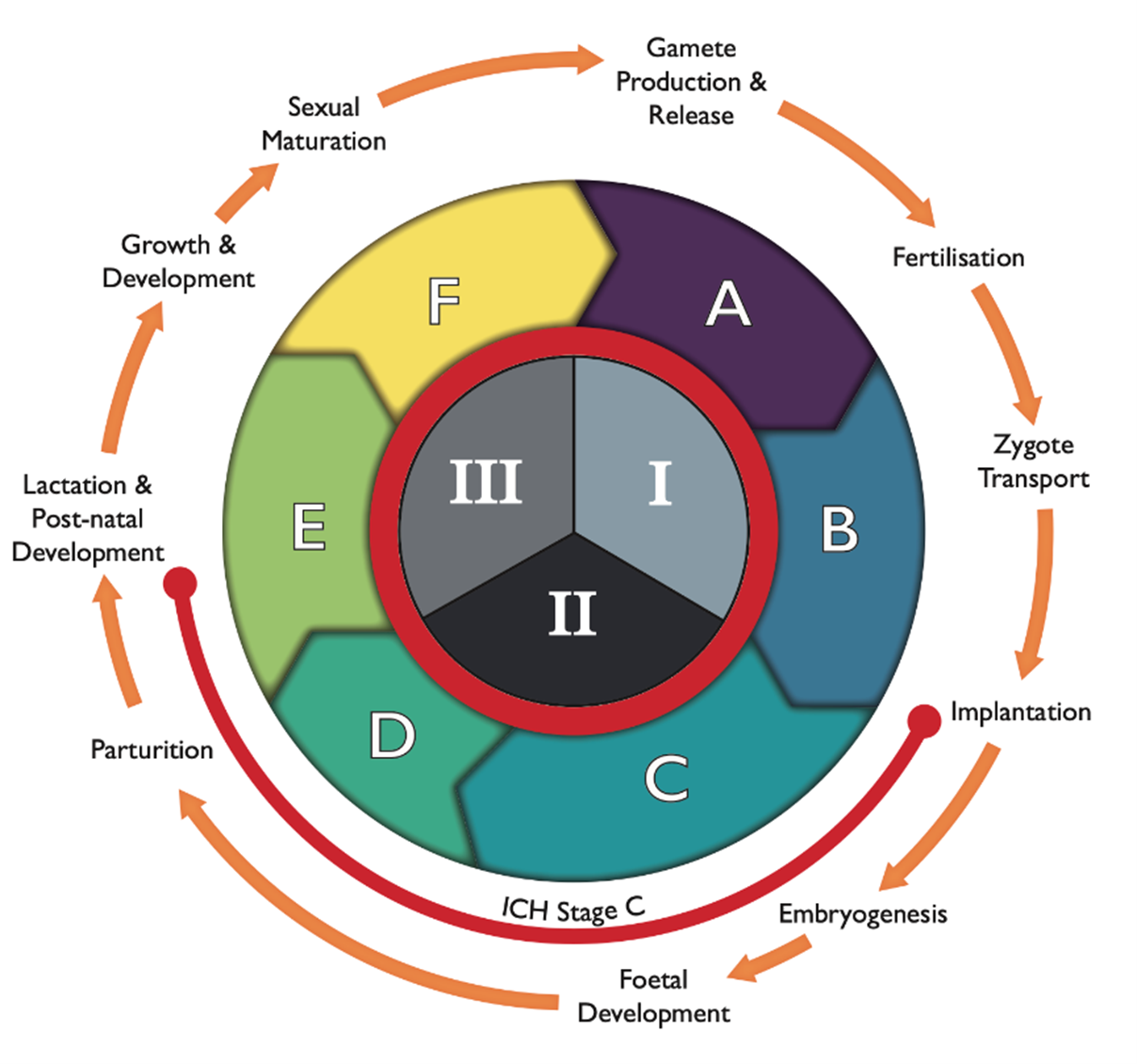

41. The COT critically appraised both EFSA’s and the BfR’s WoE approach and subsequently agreed with the BfR's selection of the key endpoint, i.e. male reproduction. However, to ensure all relevant information had been evaluated, the COT also considered evidence on reproduction published since the BfR’s assessment. The new evidence was thereby categorised using the three stages of the developmental and reproductive cycle and separated into studies of male and female biology to ensure the appropriate endpoints were reviewed in line with the WoE approached used by the BfR (Figure 1).

42. The new studies (70) on reproductive endpoints were predominantly mechanistic and/or in vitro studies. While these were supportive in providing information on the mode of action (MoA) at relatively consistent dose ranges, they did not provide any new knowledge on the MoA of BPA on reproductive effects.

43. While several of the in vivo studies focussed on interventions to ameliorate effects of BPA with various substances (including natural products), the studies by Molangiri et al. (2022) and Sturm et al. (2022) assessed male reproductive endpoints after pregnancy exposure with low concentrations of BPA, 0.4 - 40 µg/kg bw per day and 25 µg/kg bw, respectively. Molangiri et al. (2022) reported effects on male reproduction, including high plasma testosterone, thickened membranes in the testis and reduced sperm motility via impaired phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-protein kinase B (PI3K-AKT) signalling and increased testicular gene (TEX11) expression. While the MoA for BPA was different, the study suggested a window of susceptibility in utero that could have long lasting effects on male reproduction. In contrast, the study by Sturm et al. (2022) did not report any reproductive effects. While there was some change in testicular tissues, i.e. lower epithelial height of seminiferous tubules, this change did not have an impact on the apical endpoint. However, as the study was undertaken at low concentration, it added to the database around the lowest observed adverse effect level (LOAEL) and NOAEL of BPA.

44. Recent epidemiological studies were limited. Two biomonitoring studies provided further evidence of human exposure to BPA and potential risks to the population, however data on reproductive or fertility endpoints were lacking (Hwang et al., 2023; Holmboe et al., 2022). A cross-sectional study by Jeseta et al. (2024) in 385 males (17 - 62 years of age; 2019 - 2021) provided a good assessment of BPA in male semen samples. The results showed no significant correlation between traditional markers of sperm health and BPA, such as sperm concentration, volume and total sperm count, and integrity of spermatozoa deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), however, the data did show significant correlation between the concentration of BPA and decreased sperm motility and altered morphology.

45. Recent experimental data on the adverse effects of BPA on the female reproductive system reported effects on oocyte and ovarian weight as well as changes to reproductive hormones, ovarian follicles and ovarian development (Ozkemahli et al., 2022; Gonzalez-Gomez et al., 2023; Teteau et al., 2023). No evidence of causation could be established in a recent correlation study by Zhang et al. (2023) assessing BPA exposure and ovarian function and oocyte reserve in 111 women from a fertility clinic in North China from 2020 - 2021.

46. Generally, effects on the female reproductive system were seen at doses several magnitudes higher than the POD used by both EFSA and the BfR. Hence, effects on the female reproductive system have not been further considered by the COT and the Committee agreed with the BfR that a HBGV derived based on male reproductive effects would also be protective for effects on the female reproductive system.

47. Weighing all available evidence, the COT agreed with the BfR’s assessment that the adverse effect of BPA on male reproduction was the critical endpoint and should be carried forward for the derivation of a HBGV. Data published since the BfR’s assessment, while informative and adding to the overall database of BPA, did not provide any information to change the COTs current view.

Other toxicological endpoints

48. In 2023, EFSA followed a predefined protocol to derive available evidence since their 2015 evaluations; this included the evaluation of some evidence not considered in their earlier assessment (EFSA,2015). In addition to immunotoxicity and reproductive toxicity, EFSA also considered carcinogenicity, genotoxicity, hepatotoxicity and renal toxicity, cardiotoxicity, neurotoxicity and developmental neurotoxicity, developmental and reproductive toxicity, as well as effects on body weight, the lung, thyroid, parathyroid, pituitary and adrenal glands, the mammary gland, bone marrow, and haematological and metabolic effects.

49. The BfR conducted a targeted systematic literature review retrieving evidence from 2013, using the 2015 EFSA opinion as a starting point, on the reproductive and immunotoxic effects of BPA. While the review also considered metabolic effects, the available studies on increased serum uric acid were not considered suitable for a quantitative hazard assessment. The BfR however noted that there remained uncertainty over this endpoint and more data would be required. Other endpoints, e.g. effects on the liver or kidney were not included in the review as EFSA (2015; 2023) and ECHA (2014) had consistently reported the absence of adverse effects in the dose range of interest (≤ 4 µg/kg bw per day for humans). The BfR agreed with this conclusion, as well as EFSA’s conclusion that it is “unlikely to very unlikely” that BPA presented a genotoxic hazard or demonstrated tumorigenic activity. The BfR did however include and consider any new information on the toxicokinetics of BPA, due to their criticism of the factor EFSA used for the extrapolation from the critical dose in rodents to humans.

50. The COT agreed with EFSA and the BfR that BPA did not demonstrate genotoxic or carcinogenic potential and that adverse effects other than immunotoxicity or reproductive effects occurred at higher concentrations and were therefore not of direct relevance. Therefore, the in-house literature search (non-systematic) conducted by the COT in 2024 focussed on any new publications on the potential immunotoxic or reproductive effects of BPA since the publication of the BfR assessment. However, for completeness a literature search for pathology/histopathology was also included. Although the search terms were quite narrow a number of papers were retrieved which covered BPA more broadly or considered the general toxicity of BPA.

51. Two of the papers retrieved did not include primary data. Prueitte and Goodmann (2024) was a critique of the EFSA assessment, and their use of an intermediate immunotoxicity endpoint, which had not been observed in species other than mice. The authors concluded that EFSA’s new TDI was not supported by the totality of the available database on BPA but indicated that the t-TDI established by EFSA in 2015 would continue to be protective of human health. Kortenkamp et al. (2022) conducted a systematic review of BPA exposure and decline in semen quality. The authors were critical of both the EFSA and BfR assessment, stating that neither authority assessed the evidence on reproductive effects accurately. The COT noted that the review by Kortenkamp et al. (2022) focussed on reproductive endpoints only and did not include considerations on immunotoxicity or the wider potential effects of BPA. The COT reviewed the information within the paper and highlighted that the papers cited by Kortenkamp et al. (2022) to underpin their interpretation of the evidence would have been available to EFSA and the BfR at the time.

52. The COT concluded that the new evidence on general toxicity, pathology/histopathology or evidence included in the reviews/critiques highlighted above was not sufficient to alter the Committee’s current alignment with the BfR.

Considerations on the point of departure

53. EFSA (2023) derived a BMDL40 of 0.53 µg/kg bw per day based on the study by Luo et al. (2016), which exposed pregnant mice to BPA concentrations equivalent to 0.475, 4.75 and 47.5 µg/kg bw/day, as a POD for their derivation of a HBGV. The BfR (2023) derived a BMDL10 of 26 µg/kg bw per day based on a dose range of 2- 200 µg/kg bw per day (Liu et al., 2013) and a NOAEL of 50 µg/kg bw per day based on a dose range of 50-1000 µg/kg bw per day as their POD.

54. Apart from the studies by Molangiri et al. (2022) and Darmani and Alkhatib (2024) the dose ranges or PODs in the studies identified in the recent literature search were orders of magnitude higher than the PODs used by EFSA and the BfR. Molangiri et al. (2022) exposed rats to a concentration of BPA of 0.4 µg/kg bw per day, which was lower than the BMDL derived by EFSA, albeit not by much, but approximately 100-fold lower than the POD applied by the BfR. The authors reported significant effects such as an increased weight in offspring, a significant reduction in the expression of estrogen-related receptor gamma (ERRɣ) and changes in gene expression. Testicular morphology showed changes such as disoriented arrangement of seminiferous tubules, irregular-shaped Leydig cells, and a smaller number of mature sperms in lumens. Darmani and Alkhatib (2024) reported changes to serum hormone levels at a concentration of 10 µg/kg bw per day after exposure to BPA dimethacrylate (DMA). This is approximately a quarter of the NOAEL established by the BfR for BPA but still 20-fold higher than the POD applied by EFSA.

55. Although the effects reported in the study by Darmani and Alkhatib (2024) were at a concentration lower than the POD established by the BfR, they were based on BPA-DMA, rather than BPA itself. Hence, while these provide an indication of adverse effects, it is not clear whether the effects seen with BPA-DMA are consistent with effects of BPA seen at the same concentration. The effect dose was still higher than the POD applied by EFSA. While results by Molangiri et al. (2022) were in line with previous studies, demonstrating adverse effects on male offspring after in utero exposure, albeit at lower levels, the focus of the study was predominantly on BPS. Additional data would be required to fully establish whether the reported effects could be consistently seen at the reported dose levels.

56. While both studies contributed to the overall knowledgebase, the COT did not consider the evidence sufficient to reconsider their current alignment with the BfR or that the TDI would not be sufficiently protective of adverse effects of BPA.

Derivation of the TDI

57. Both EFSA and the BfR acknowledged that the interpretation of the available evidence and divergence in the risk assessment were linked to the tools and methodologies applied. The key points of divergence were the adverse effect definition, the inclusion/exclusion of scientific information, the use of an apical versus intermediate endpoint, uncertainty analysis and HEDF.

58. To derive the POD for the derivation of the HBGV the BfR undertook BMD modelling on all relevant studies. While the effects on male reproduction were considered the critical endpoint, immunotoxicological studies were also submitted to BMD modelling to evaluate to which extent the HBGV would also be protective for immunological effects. Weighing all evidence, the BfR based their derivation of the TDI on the effect dose for reduced sperm count in two sub-chronic studies in rats (Liu et al., 2013; Srivastava and Gupta, 2018). Studies where the NOAEL was the highest dose tested were excluded from further assessment as it was unclear at which dose, if any, a BMR would have been reached. The two selected studies were submitted to a probabilistic uncertainty assessment according to the approach by the World Health Organisation (WHO IPCS, 2017). Differently to EFSA’s deterministic approach, the distribution of possible HEDs resulting from toxicokinetic data were thereby combined with typical distributions for other uncertainties.

59. Both EFSA and the BfR extrapolated the reference point (RP) to the TDI by substituting the toxicokinetic standard subfactor for interspecies extrapolation by a BPA-specific HEDF. The COT noted that both authorities applied the same human data, however the animal studies they used differed. This difference in animal studies resulted in HED values differing by two orders of magnitude, which in turn, together with the different approaches to the derivation of the TDI (deterministic versus probabilistic), led to the difference in magnitude for the resulting HBGV. The approach taken by the BfR comprised a significant degree of conservatism in the derivation of the TDI, however, the COT deemed the overall assessment to have avoided unnecessary conservatism.

60. While the COT acknowledged that there was clear evidence of BPA causing an effect on the immune system, the evidence as a whole was not strong enough to support immunotoxicity as the critical endpoint. However, the TDI derived by the BfR would still be protective of a significant increase in the respective intermediate endpoint, as well as protective with respect to other toxicological endpoints. Based on the current body of evidence, adverse immunological effects in humans, or other toxicological effects were unlikely to result from exposures in the range of the TDI of 0.2 μg/kg bw per day and would require higher exposure concentrations.

Considerations on the exposures of UK consumers

61. In line with EFSA and the BfR, the COT highlighted that the most recent exposure data predated the 2015 EFSA opinion. A comparison of the t-TDI with exposure estimates in 2015 found no health concern for any age group from dietary exposure and low health concern (i.e. considered unlikely to cause adverse health effects) from aggregate exposure to BPA. While EFSA was not explicitly asked to perform an exposure assessment in their 2023 evaluation, using the exposures estimated from 2015 would lead to exceedances of approximately 2-3 orders of magnitude. However, EFSA noted that the data used in their 2023 evaluation may not accurately reflect the current exposure scenarios of consumers. Both, the BfR and the COT agreed with the uncertainties in this approach. The BfR did not undertake an exposure assessment in their evaluation and both the BfR and the COT stressed the importance of updated occurrence levels to fully assess any potential risks to consumers.

62. While adopting the TDI set by the BfR was a precautionary approach, the COT highlighted that having an up-to-date exposure assessment would further mitigate any potential risk as it would provide an up to date picture of the current UK exposures and provide evidence compared to EFSA’s more stringent approach.

Overall conclusion by the COT

In this guide

In this guideThis is a background paper for discussion. It has not been finalised and should not be cited.

63. Following the publication of the most recent EFSA evaluation (2023), the COT agreed that there was a requirement to assess the new evidence on BPA and adjust the current TDI. To ensure timely consumer protection, rather than undertaking a lengthy assessment, the COT instead assessed the weighing of evidence and approaches taken by both EFSA and the BfR. However, a non-systematic literature search was also undertaken to ensure no new data had been published since the BfR assessment in 2023.

64. The COT agreed with EFSA and the BfR that adverse effects of BPA, other than immunological effects and effects on reproduction, occurred at higher concentrations and were therefore not of direct relevance, i.e. a HBGV derived on either of these endpoints would also be protective for other toxicological effects. The COT was further in agreement that BPA did not demonstrate genotoxic or carcinogenic potential.

65. While the COT acknowledged that there was a clear effect of BPA on the immune system, the evidence, i.e. effects on an intermediate endpoint, was not sufficient to consider immunotoxicity as the key adverse effect. The available data were not sufficiently robust to demonstrate a clear progression from an intermediate endpoint to a continuous apical effect. The COT instead agreed with the BfR that adverse effects on male reproduction, i.e. sperm count and motility, were the critical endpoint and should be applied to derive a HBGV. This was in line with previous COT assessments.

66. The studies published since the BfR assessment were informative and added to the overall knowledge base, but did not contain sufficient evidence to alter the view of the COT regarding the critical endpoint or effect dose.

67. Although the COT considered the BfR’s TDI highly conservative, in comparison to EFSA’s, their approach avoided unnecessary conservatism. Hence, after evaluating the available information, the COT considered the endpoint selected and approach applied by the BfR scientifically robust and hence agreed to adopt the TDI of 0.2 µg/kg bw per day derived by the BfR.

COT Evaluation Timeline

In this guide

In this guideThis is a background paper for discussion. It has not been finalised and should not be cited.

Discussion of the Draft EFSA Opinion (2022; TOX/22/11-16).

Discussion of the EFSA 2023 Opinion (TOX/23/25); COT First draft interim position statement.

TOX/23/45: Second draft interim position statement on bisphenol A.

TOX/23/50: Third draft interim position statement on bisphenol A.

TOX/23/61: Bisphenol A: The Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), BPA Part 2.

TOX/24/08: Fourth draft interim position paper on bisphenol A.

TOX/24/13: Fifth Draft Interim Position Statement on Bisphenol A.

TOX/24/19: Sixth draft interim position statement on bisphenol A.

COT Position Paper on Bisphenol A (BPA).

COT supplementary statement

December 2025

Abbreviations

In this guide

In this guideThis is a background paper for discussion. It has not been finalised and should not be cited.

|

AKT |

Protein kinase B |

|

Anti-OVA |

Anti-ovalbumin |

|

AOP |

Adverse outcome pathway |

|

APROBA |

Approximate probabilistic analysis (tool) |

|

BMD |

Benchmark dose |

|

BMDL |

Lower confidence level of the benchmark dose |

|

BMDR |

Benchmark dose response |

|

BPA |

Bisphenol A |

|

BPS |

Bisphenol S |

|

bw |

Bodyweight |

|

DMA |

Dimethacrylate |

|

DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

|

DNELs |

Derived no effect levels |

|

ERRɣ |

Estrogen-related receptor gamma |

|

FCM |

Food Contact Materials |

|

GLP |

Good laboratory practise |

|

HBGV |

Health based guidance value |

|

HED(F) |

Human equivalent dose (factor) |

|

IFN-ɣ |

Interferon gamma |

|

IgA |

Immunoglobulin A |

|

IL-17/21/6/23/4/3 |

Interleukin-17/21/6/23/4/3 |

|

LOAEL |

Lowest observed adverse effect level |

|

MLN |

Mesenteric lymph nodes |

|

MoA |

Mode of action |

|

NOAEL |

No observed adverse effect level |

|

OEL |

Occupational exposure limit |

|

PC |

Polycarbonates |

|

PI3K |

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

|

POD |

Point of departure |

|

RP |

Reference point |

|

SLE |

Systemic lupus erythematosus |

|

SML |

Specific migration limit |

|

t-TDI |

Temporary tolerable daily intake |

|

TNF-α |

Tumour necrosis factor alpha |

|

UF |

Uncertainty factor |

|

WoE |

Weight of evidence |

|

BfR |

German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment |

|

CEP |

EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials, Enzymes and Processing Aids |

|

COT |

Committee on Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment |

|

EC |

European Commission |

|

ECHA |

European Chemicals Agency |

|

EFSA |

European Food Safety Authority |

|

EFSA CEP Panel |

EFSA’s Panel on Food Contact Materials, Enzymes and Processing Aids |

|

EMA |

European Medical Agency |

|

EU |

European Union |

|

FDA |

United States Food and Drug Administration |

|

IPCS |

International Programme on Chemical Safety |

|

OECD |

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

|

UK |

United Kingdom |

|

WHO |

World Health Organisation |

References

In this guide

In this guideThis is a background paper for discussion. It has not been finalised and should not be cited.

BfR (2023). Bisphenol A: BfR proposes new health based guidance value, current exposure data are needed for a full risk assessment. BfR Opinion No 018/2023.

https://doi.org/10.17590/20230419-114234-0

Bodin J, Bolling Ak, Becher R, Kuper F, Lovik M, Nygaard UC (2014). Transmaternal bisphenol A exposure accelerates diabetes type 1 development in NOD mice. Toxicological Science, 137(2), 311-323.

https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kft242

Camacho L, Lewis SM, Vanlandingham MM, Olson GR, Davis KJ, Patton RE, Twaddle NC, Doerge DR, Churchwell MI, Bryant MS, McLellen FM, Woodling KA, Felton RP, Maisha MP, Juliar BE, Gamboa da Costa G, Delclos KB (2019). A two-year toxicology study of bisphenol A (BPA) in Sprague-Dawley rats: CLARITY-BPA core study results. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 132, 110728.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2019.110728

COT (2024). Position paper on bisphenol A.

https://doi.org/10.46756/sci.fsa.sjl259

Darmani H and Alkhatib MMA (2024). Non-monotonic effects of bisphenol A dimethacrylate on male mouse reproductive system and fertility leads to impaired conceptive performance. Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods, 34(3), 262-270.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15376516.2023.2279723

Dere E, Anderson LM, Huse SM, Spade DJ, McDonnell-Clark E, Madnick SJ, Hall SJ, Camacho L, Lewis SM, Vanlandingham MM, Boekelheide K (2018). Effects of continuous bisphenol A exposure from early gestation on 90 day old rat testes function and sperm molecular profiles: A CLARITY-BPA consortium study. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 347, 1-9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2018.03.021

Dong Y, Gao L, Sun Q, Jia L, Liu D (2023). Increased levels of IL-17 and autoantibodies following Bisphenol A exposure were associated with activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and abnormal autophagy in MRL/lpr mice. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 255, 114788.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.114788

EFSA (2015). Scientific Opinion on the risk to public health related to the presence of bisphenol A (BPA) in foodstuffs. EFSA Journal, 13(1), 3978. Publications | EFSA

EFSA and BfR (2023). Report on diverging views between EFSA and BfR on EFSA’s updated bisphenol A assessment. Report on diverging views between EFSA and BfR on EFSA bisphenol A (BPA) opinion

EFSA and EMA (2023). Report on divergent views between EFSA and EMA on EFSA’s updated bisphenol A assessment. ema-efsa-article-30.pdf

EFSA (2024). Re-evaluation of the risk to public health related to the presence of bisphenol A (BPA) in foodstuffs. EFSA Journal, 21(4), 6857, 392 pp.

https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2023.6857

FDA (1966). Guidelines for reproduction studies for safety evaluation of drugs for human use. Washington, Department of Health, Education and Welfare. Referenced in: Raheja KL, Jordan A, Fourcroy JL (1988). Food and drug administration guidelines for reproductive toxicity testing. Reproductive Toxicology, 2(3-4), 291-293.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0890-6238(88)90034-2

FDA (2014). Updated safety assessment of Bisphenol A (BPA) for use in food contact applications. download

FDA (2021). S5(R3) Detection of reproductive and developmental toxicity for human pharmaceuticals. Guidance for industry. The International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). Guidance for Industry

FDA (2024). Memorandum on the request for consultation on bisphenol A (BPA). (unpublished)

Gonzalez-Gomez M, Reyes R, Damas-Hernández MdC, Plasencia-Cruz X, González-Marrero I, Alonso R, Bello AR (2023). NTS, NTSR1 and ERs in the pituitary-gonadal axis of cycling and postnatal female rats after BPA treatment. International Journal of Molecular Science, 24, 7418

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087418

Gu HJ, Kim DY, Shin SH, Rahman MdS, Lee H-S, Pang M-G, Kim J-M, Ryu B-Y (2024). Genome-wide transcriptome analysis reveals that Bisphenol A activates immune responses in skeletal muscle. Environmental Research, 252(3), 119034.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.119034

Holmboe S, Scheutz Henriksen L, Frederiksen H, Andersson A-M, Priskorn L, Jorgsen N, Juul A, Toppari J, Skakkabaek NE, Main KM (2022). Prenatal exposure to phenols and benzophenols in relation to markers of male reproductive function in adulthood. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 13.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1071761

Hwang M, Park S-J, LeeH-J (2023). Risk assessment of bisphenol A in the Korean general population. Applied Science, 13, 3587.

https://doi.org/10.3390/app13063587

IPCS (2001). Principles for evaluating health risks to reproduction associated with exposure to chemicals. Environmental Health Criteria, 225. Principles For Evaluating Health Risks To Reproduction Associated With Exposure To Chemicals (EHC 225, 2001)

Jeseta M, Kalina J, Franzova K, Fialkova S, Hosek J, Mekinova L, Crha I, Kempisty B, Ventruba P, Navratilova J (2024). Cross sectional study on exposure to BPA and its analogues and semen parameters in Czech men. Environmental Pollution, 345, 123445.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2024.123445

Kortenkamp A, Martin O, Ermler S, Baig A, Scholze M (2022). Bisphenol A and declining semen quality: A systematic review to support the derivation of a reference dose for mixture risk assessments. International Journal of Hygine and Environmental Health, 241, 113942.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2022.113942

Liu C, Duan W, Li R, Xu S, Zhang L, Chen C, He M, Lu Y, Wu H, Pi H, Luo X, Zhang Y, Zohong M, Yu Z, Zhou Z (2013). Exposure to bisphenol A disrupts meiotic progression during spermatogenesis in adult rats through estrogen-like activity. Cell Death and Disease 4 (6).

https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2013.203

Luo S, Li Y, Zhu Q, Jiang J, Wu C, Shen T (2016). Gestational and lactational exposure to low-dose bisphenol A increases Th17 cells in mice offspring. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 47, 149-158.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2016.09.017

Malaise Y, Menard S, Cartier C, Lencina C, Sommer C, Gaultier E, Houdeau E, Guzylack-Piriou L (2018). Consequences of bisphenol a perinatal exposure on immune responses and gut barrier function in mice. Arch Toxicol 92 (1), 347-358.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-017-2038-2

Menard S, Guzylack-Piriou L, Lencina C, Leveque M, Naturel M, Sekkal S, Harkat C, Gaultier E, Olier M, Garcia-Villar R, Theodorou V, Houdeau E (2014a). Perinatal exposure to a low dose of bisphenol A impaired systemic cellular immune response and predisposes young rats to intestinal parasitic infection. PLoS One, 19(11), e112752.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112752

Menard S, Guzylack-Piriou L, Leveque M, Braniste V, Lencina C, Naturel M, Moussa, L, Sekkal S, Harkat C, Gaultier E, Theodorou V, Houdeau E (2014b). Food intolerance at adulthood after perinatal exposure to the endocrine disruptor bisphenol. The FASEB Journal, 28(11), 4893-4900.

https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.14-255380

Molangiri A, Varma S, Satyavani M, Kambham S, Duttory AK, Basak S (2022). Prenatal exposure to bisphenol S and bisphenol A differentially affects male reproductive system in the adult offspring. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 16, 113292.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2022.113292

O’Brian E, Bergin IL, Dolinoy DC, Zaslona Z, Little RJA, Tao Y, Peters-Golden M, Manusco P (2014). Perinatal bisphenol A exposure beginning before gestation enhances allergen sensitisation, but not pulmonary inflammation, in adult mice. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, 5(2), 121-131.

https://doi.org/10.1017/s204017441400004x

Ozkemahli G, Ozyurt AB, Erkekoglu P, Zeybek ND, YersalN, Kocer-Gumusel B (2022). The effects of prenatal and lactational bisphenol A and/or di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate exposure on female reproductive system. Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods, 32(8), 597-605

https://doi.org/10.1080/15376516.2022.2057265

Prueitte RL and Goodmann JE (2024). Evidence evaluated by European Food Safety Authority does not support lowering the temporary tolerable daily intake for bisphenol A. Toxicological Sciences, 198(2), 185-190.

https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfad136

RIVM (2014). Bisphenol A. Part 1. Facts and figures on human and environmental health issues and regulatory perspectives. RIVM Report 601351001/2014. Bisphenol APart 1. Facts and figures on human and environmental health issues and regulatory perspectives

RIVM (2016). Bisphenol A. Part 2. Recommendations for risk assessment. RIVM Report 2015-0192. Bisphenol A, Part 2 Recommendations for risk management

Spielmann H (2009). The way forward in reproductive/developmental toxicity testing. Alternatives to Laboratory Animals, 37(6), 641-656.

https://doi.org/10.1177/026119290903700609

Srivastava S and Gupta P (2018). Alteration in apoptotic rate of testicular cells and sperms following administration of Bisphenol A (BPA) in Wistar albino rats. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 25 (22), 21635-21643.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-2229-2

Sturm S, Weber K, Klinc P, Spörndly-Ness E, Fakhrzadeh A, Knific T, Skibin A, Fiolova V, Okazaki Y, Razinger T, Laufs J, Kreutzer R, Pogacnik M, Svara T, Cerkvenik-Flajs V (2022). Basic exploratory study of bisphenol A (BPA) dietary administration to istrian pramenka rams and male toxicity investigation. Toxics, 10, 224.

https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics10050224

Teteau O, Carvalho AV, Papillier P, Mandon-Pepin B, Jouneau L, Jarrier-Gaillard P, Sedmarchais A, Lebalchelier de la Riviere ME, Vignault C, Maillard V, Binet A, Uzbekova S, Elis S (2023). Bisphenol A and bisphenol S both disrupt ovine granulosa cell steroidogenesis but through different molecular pathways. Journal of Ovarian Research, 16(30).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-023-01114-4

WHO/IPCS (2017). Guidance document on evaluating and expressing uncertainty in hazard characterisation. Second Edition. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

Ye X, Liu Z, Han HW, Noh JY, Shen Z, Kim DM, Wang H, Guo H, Ballard J, Golovko a, Morpurgo B, Sun X (2023). Nutrient-sensing ghrelin receptor in macrophages modulates bisphenol A-induced intestinal inflammation in mice. Genes, 14, 1455.

https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14071455

Zhang N, Zhao Y, Zhai L, Bai Y, Jia L (2023). Urinary bisphenol A and S are associated with diminished ovarian reserve in women from an infertility clinic in Northern China. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 256, 114867.

Literature search on the reproductive toxicity, immunotoxicity, pathology and histopathology of BPA

In this guide

In this guideThis is a background paper for discussion. It has not been finalised and should not be cited.

A literature search was performed from January 2022 until June 2024 using the following search terms:

(Bisphenol A OR BPA) AND (reproduct* OR immunotox* OR patholog* OR histopatholog* OR Th17).

The search returned 761 articles, of which 3 were duplicates. After manual filtering (titles and abstracts) 101 articles remained:

- Broader BPA studies (4),

- Immune effects of BPA (10),

- Reproductive effects of BPA (70),

- Pathology/histopathology (8),

- Other toxic effects (9).