Statement on the potential risks from ergot alkaloids in the maternal diet

Background and Introduction

In this guide

In this guideBackground

1. The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) last considered maternal diet and nutrition in relation to offspring health, in its reports on ‘The influence of maternal, fetal and child nutrition on the development of chronic disease in later life’ (SACN, 2011) and on ‘Feeding in the first year of life’ (SACN, 2018). In the latter report, the impact of breastfeeding on maternal health was also considered. In 2019, SACN agreed to conduct a risk assessment on nutrition and maternal health focusing on maternal outcomes during pregnancy, childbirth and up to 24 months after delivery; this would include the effects of chemical contaminants and excess nutrients in the diet.

2. SACN agreed that, where appropriate, other expert Committees would be consulted and asked to complete relevant risk assessments e.g., in the area of food safety advice, and this was referred to the Committee on the Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment (COT). The subject was initially discussed by the COT during the horizon scanning item at the January 2020 meeting with a scoping paper being presented to the Committee in July 2020. This included background information on a provisional list of chemicals proposed by SACN. It was noted that this was subject to change following discussion by COT, who would be guiding the toxicological risk assessment process: candidate chemicals or chemical classes can be added or removed as the COT considered appropriate. The list was brought back to the COT with additional information in September 2020. Following a discussion at the COT meeting in September 2020, it was agreed that papers on a number of components should be prioritised. Of the groups prioritised was ergot alkaloids (EAs) and the following paper provides the advice of the COT on whether exposure to EAs would pose a risk to maternal health.

Introduction

3. EAs are secondary metabolites produced by the fungi families Clavicipitaceae and Trichocomaceae, with Claviceps purpurea being the most widespread EA producing species in Europe. Infection by these fungi can affect more than 400 plant species, including some economically important cereal grains such as rye, wheat, triticale, barley, millet and oats (Agriopoulou, 2021).

4. The biological effects of EAs have been known for centuries, including their traditional use in obstetrics. Consumption of contaminated grains, flour or bread caused severe epidemics of a condition known as Erysipelas or St. Anthony’s fire. Since the first systematic investigations in the 1900s, many natural EAs and their synthetic analogues have been used as pharmaceutical agents to treat central nervous system diseases (Tasker and Wipf, 2021).

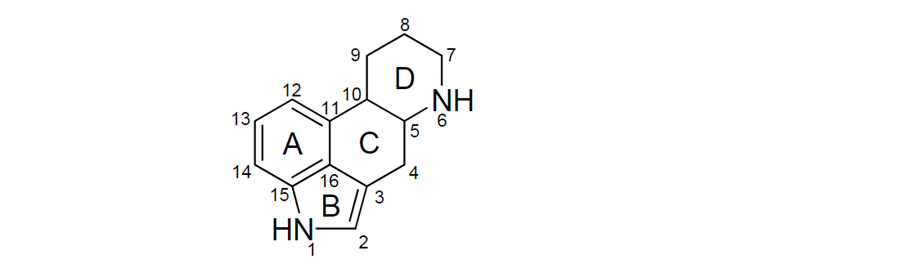

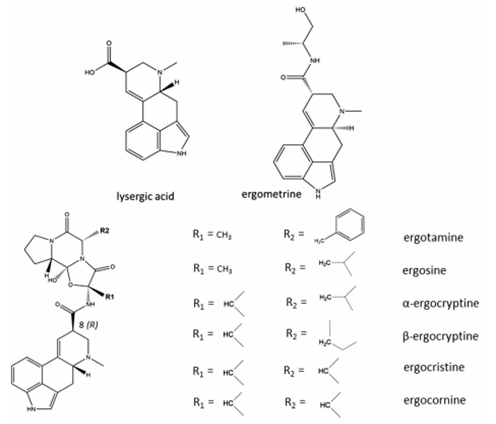

5. Most of the naturally occurring EAs contain a tetracyclic ergoline ring system (Figure 1) consisting of four fused rings with the N6 position carrying a methyl group, and a double bond at either C8,9 or at C9,10 (EFSA, 2012). There are 80 different naturally occurring EAs (Schiff, 2006). Based on their occurrence and the available toxicological data, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) considered six EAs in their risk assessment in 2005, namely ergotamine, ergocornine, α-ergocryptine, ergosine, ergocristine (peptide ergot alkaloids) and ergometrine (a lysergic acid amide). For Δ9,10-ergolenes the asymmetric centre at C8 (Figure 1) gives rise to two epimers, with a double bond at C9/10, β-Δ9,10-ergolenes (suffix -ine) and α-Δ9,10-isoergolenes (suffix -inine). While the -inine forms of EAs are considered biologically inactive, interconversion occurs frequently and hence EFSA included both forms of EAs (-ine and inine) in their assessment (EFSA, 2005, Tasker and Wipf, 2021).

Figure 1: Ergoline ring system including numbering and assignment of ring (EFSA, 2012).

6. A number of derivatives of EAs have been developed for use (or potential use) as pharmacological agents. Bromocriptine is a synthetic ergoline derivate and is used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and pituitary tumours (Hardman et al., 2001). Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) is a semi-synthetic derivative of the EA-family, first produced in the 1950s. This illegal drug has worldwide recreational (ab)use and is known to cause psychoactive effects. Ergometrine is a derivate of lysergic acid (LA) used primarily in obstetrics.

7. Other EAs considered in this evaluation were peptide alkaloids with a cyclized tripeptide as a substituent at C8 (EFSA, 2012, JECFA, 2023). The chemical structures of the most prevalent EAs are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Chemical structures of the most prevalent EAs (JECFA, 2023).

Toxicity

In this guide

In this guide8. EAs modulate the function of noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin neurotransmitters. The structural similarities of EAs to these neurotransmitters allow them to activate or block the neurotransmitter receptors and modify neurotransmitter release and reuptake. EAs produce peripheral effects such as uterine contractions and vasoconstriction, and central nervous system (CNS) effects such as induction of hypothermia and emesis. (Arroyo-Manzanares et al., 2017; Cassady et al., 1974; EFSA, 2012; Fitzgerald and Dinan, 2008; Schardl et al., 2006).

Toxicokinetics

9. In both humans and experimental animals EAs are incompletely absorbed from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the intestinal absorption of hydrogenated ergot peptide alkaloids generally varying between 10 and 30 %. EAs are subjected to oxidative biotransformation, involving cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4), via hydroxylation in the liver. However, while EAs are metabolised by CYP3A4 they can also inhibit its activity (Aellig et al., 1977; Eckert et al., 1978; Little et al., 1982; Olver et al., 1980; Wyss et al., 1991).

10. Studies have shown that P450 monooxygenase and its clusters play a key role in the biosynthesis of many EAs, with clavine oxidase (CloA) playing a role in EAs that are derivatives of LA (Gerhards et al., 2014, Haarmann et al., 2006; Mulac and Humpf, 2011; Young et al., 2015).

11. No studies were available on the toxicokinetics of dietary EAs in humans. However, human data were available on ergotamine used as a pharmaceutical to treat Parkinson’s disease. Absorption of ergotamine from the GI tract was poor after oral/sublingual administration and bioavailability was further reduced by high pre-systemic hepatic metabolism. Ergotamine tartrate can also be given rectally to improve absorption, yet bioavailability is still ≤ 5 %. Caffeine is sometimes included in oral and rectal preparations in an effort to improve absorption; the effectiveness of this is, however, still unclear (Silberstein and McCrory, 2003; Tfelt-Hansen et al., 2000).

Acute Toxicity

12. Species differ in their sensitivity to EAs, rabbits being the most sensitive species with lethal dose (LD)50 values between 0.9 and 3.2 mg/kg body weight (bw) following intravenous (i.v.) injection. The LD50s were determined for a series of naturally occurring and (semi-) synthetic EAs by i.v., subcutaneous (s.c.) and oral exposures (in 2 % gelatine) in mouse, rat and rabbit (Griffith et al., 1978). All naturally occurring EAs demonstrated a low oral acute toxicity compared to i.v. administration, indicating low absorption and high pre-systemic metabolism via the oral route. Based on the oral LD50s (27.8 – 1200 mg/kg), EFSA concluded that, overall, EAs exhibit moderate oral acute toxicity (EFSA, 2012).

13. In repeat oral dose studies in rats there were no significant differences in the toxicity of ergotamine, ergometrine and α-ergocryptine, with no-observed-adverse effect levels (NOAELs) ranging from 0.22 - 0.60 mg/kg bw per day (EFSA, 2012).

14. Exposure to cereal grains contaminated with EAs can lead to a condition called ergotism (Guggisberg, 2003). There are two main types of ergotism, gangrenous and convulsive. The gangrenous form is caused by the strong vasoconstrictive properties of some EAs, which result in restriction of blood flow to peripheral parts of the body (ischemia). In the convulsive form, tingling is followed by neurotoxic symptoms such as hallucinations, delirium, and epileptic-type seizures. It has been suggested that as well as a high concentration of EAs, a deficiency in vitamin A could be a causative factor inducing convulsive ergotism. Additional symptoms of ergotism are lethargy and depression (Arroyo-Manzanares et al., 2017; EFSA, 2012).

15. Because EAs act on several neurotransmitter receptors, particularly adrenoceptors, dopamine and serotonin receptors, EFSA considered neurotoxicity to be their main acute effect, with symptoms such as restlessness, miosis or mydriasis (contraction and dilation of the pupils), muscular weakness, tremor and rigidity in mammals. In humans, acute effects are directly related to receptor antagonism and include diarrhoea, and loss of consciousness.

Chronic toxicity

16. A study by Valente et al. (2020) reported a decrease in serum 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) levels in bovine species fed dietary concentrations of egrovaline for 15 days (0, 0.862, 1.282 mg/kg dry diet ad libitum) or dosed directly into the rumen with ergovaline for 7 days (15 µg/kg bw).

17. A study by Korn et al. (2014) reported spontaneous alopecia, erosions, crusts and necrosis, specifically of the tail area, which occurred exclusively in young rabbits aged 113 ± 20 days (14 out of 103 rabbits) from a colony fed with hay and a commercial pelleted feed. The results of the study indicated that EAs may have been the cause of the tail necrosis, with immunoassays on blood samples showing a mean and maximum EAs concentration of 410 µg/kg and 1,700 µg/kg, respectively. In addition, EAs were detected in the faeces of the affected rabbits at levels up to 200 μg/kg. The mean and maximum dietary intakes of total EAs were 17 and 71 μg/kg bw, respectively. Other toxins, such as fusarium toxin, were also detected in the feed, but at levels which, according to the authors, did not explain the observed effects.

18. Repeated dosing with various EAs, resulted in ischaemia, particularly in the extremities (e.g., tails) of rats, decreased body weight gain and changes in the levels of some hormones such as follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) (Janssen et al. 2000; JECFA, 2023). Tail gangrene was observed in rats 5 - 7 days after a single i.p. exposure to 25 mg/kg bw ergotoxine (a mixture including ergocornine, α- and β-ergocryptine, and ergocristine) (Griffith et al., 1978). The NOAELs were 0.22 - 0.60 mg/kg bw per day. No major quantitative difference in the toxicity of ergotamine, ergometrine and α-ergocryptine was observed (EFSA, 2012; JECFA, 2023).

19. No data were available on the chronic toxicity of EAs from dietary exposure in humans. However, limited information was available from the use of ergot containing medications. Case studies of long-term use of EA medication (doses from 1 to 2 mg ergotamine titrate) for migraine headaches reported severe lower extremity claudication (pain in the limbs) due to chronic arterial insufficiency (Bogun et al., 2011; Fröhlich et al., 2010; Garcia et al., 2000; Silberstein and McCrory, 2003). In all instances treatment was discontinued and patients were also asked to discontinue the use of caffeine and cigarettes. Anti-platelet therapy was used to successfully reverse the symptoms.

20. To minimize toxicity and avoid adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, weakness, muscle pains, paraesthesiae and coldness of the extremities from acute migraine treatment with ergotamine, it was recommended that the maximum dose should not exceed 10 mg per week. (Orton and Richardson, 1982; Perrin et al., 1985).

21. Bromocriptine is a synthetic compound with an affinity to dopamine receptors due to its structural similarities to a variety of EAs. It is therefore used as a treatment for Parkinson’s disease and to supress prolactin levels. However, several case reports, involving a total of 510 patients, showed adverse side effects in 34 % of patients with Parkinson’s disease receiving high doses of bromocriptine, 31-100 mg/day (Bernard et al., 2015). A number of severe adverse events were also reported in patients receiving bromocriptine for suppression of lactation (Lieberman and Goldstein, 1985).

Genotoxicity and Carcinogenicity

22. No genotoxicity effects were demonstrated for ergotamine tartrate (Et) in a Salmonella typhimurium (St) assay (10-10,000 µg/plate for 48 hours) and mouse lymphoma TK+/- assay (7.7-108 µg/mL for 4 hours) (Seifried et al., 2006). Roberts and Rand (1977) reported that ergotamine induced chromosomal abnormalities in human lymphocytes and leukocytes in vitro. In a study by Dighe and Vaidya (1988) ergotamine, ergonovine and methylergonovine induced sister chromatid exchange (SCE) frequencies in vitro in cultured Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, while ergocristine and α-ergocryptine showed a weak and no effect, respectively.

23. Due to limited and contradictory data on the genotoxic and mutagenic effects of EAs, EFSA considered the available genotoxicity studies to be insufficient, except for ergotamine, concluding that the available data on ergotamine did not indicate bacterial or mammalian cell mutation (EFSA, 2012). Taking into account all the available information, the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA, 2023) concluded that naturally occurring EAs do not raise concerns for genotoxicity.

24. Bromocriptine has been shown to cause an increase in uterine tumours in rats, due to its inhibition of prolactin secretion, with a lifetime of relative hyperprolactinemia. However, as the mechanism proposed in the rat is the reduced luteotrophic effect of prolactin, and due to the distinctly different mechanisms involved in female reproductive hormonal regulation between humans and rat, the mode of action for these tumours in the rat is generally considered to have no relevance to humans (Harleman et al., 2012).

25. EAs are not considered to pose a carcinogenic risk to humans (EFSA, 2012; JECFA, 2023) but they have not been assessed by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). However, they have been suggested to be possible cytostatic agents, with a possible role as anti-cancer agents (De Ruyck et al., 2015). Experiments in rodents showed that ergotamine, ergocryptine and ergocornine were able to suppress the growth of pituitary tumours in vivo (MacLeod and Lehmeyer, 1973)

26. More recently a range of mRNA microarray studies investigating the cytotoxic activity of EAs on a range of human cancer cell types reported strong inhibitory effects for 1-propylagroclavine and dihydroergocristine against genes associated with the progression of leukaemia. The cytotoxicity pathway is not yet fully understood, but preliminary results suggested that EAs have the potential to be used for the treatment of otherwise drug-resistant and refractory tumours via the inhibition of prolactin release from the anterior pituitary gland (Cassady et al., 1974; Mrusek et at., 2015).

Reproductive and Developmental toxicity

Reproductive effects in animals

27. EAs have a number of well-established effects on the reproductive process in rodents, including prevention of pregnancy, predominantly due to interference with implantation, and embryotoxicity. These adverse effects in rodents have generally been observed at higher doses than the lowest-observed-adverse-effect levels (LOAELs) in the repeat dose studies (EFSA, 2012).

28. Effects on FSH levels were observed in rats fed a 0, 4, 20, 100 or 500 mg ergocryptine/kg diet for 28 - 32 days. In females there was trend for FSH to decrease with dose, but there was appreciable variation and this was not statistically significant, while in males there was no consistent effect. There was a dose-dependent increase in LH in males but not in females. Prolactin levels were significantly decreased in both males and females at dose above 4 mg/kg bw per day. There was a decrease in thyroxine (T4) levels in both sexes, with males more sensitive than females (Janssen et al., 2000).

29. Cows that were exposed to EAs via tall fescue grazing had a 41 % lower conception rate than those grazing an EA-free pasture. The period of concern for EA negatively affecting conception was identified as the time between ovulation and the first six days of embryonic development (Klotz et al., 2019). EAs were also shown to directly alter bovine sperm motility and morphology, indicating that EAs may hinder cattle reproductive rates (Page et al., 2019).

30. Three yearling colts were fed a diet rich in EAs for 80 days. Four colts were fed a control diet. In spermatocytes from colts fed EAs, there was a significant, deleterious effect in the establishment and/or maintenance of partial synapsis of the sex chromosomes. The authors suggested that exposure of colts, prior to maturity, could impair or alter normal sexual maturation, which lead to fertility issues when these colts became sexually mature. There was little or no effect in mature stallions. (Fayrer-Hosken et al., 2012; 2013).

31. Studies in livestock also reported reduced reproductive performance, particularly in female cattle, after EAs exposure. Regional vasoconstriction and corresponding decreased blood flow to reproductive tissues was observed, along with a decreased dry matter intake, and/or increased body temperature, leading the authors to conclude that the effect of EAs was both direct and indirect (Poole and Poole, 2019).

32. Limited information was available on the effects of EAs exposure during pregnancy itself, in particular the effects on the vascular system supporting the growing fetus. A study by Duckett et al. (2014) examined fetal growth in sheep following maternal exposure to EAs at a concentration of 0.8 µg/g diet of ergovaline during gestation, this is the equivalent to 0.011 μg/kg bw per day based on a body weight of 70 kg. Exposure to EAs during mid and/or late gestation in ewes reduced fetal growth. A more recent study in ewes indicated that maternal blood supply to the placenta appeared to be resistant from adverse effects of EAs, but umbilical vasculature was not, which could adversely influence normal fetal growth (Klotz et al., 2019). In utero exposure to EAs in pregnant ewes, especially during phase two of gestation altered fetal growth, muscle fibre formation, and micro ribonucleic acid (miRNA) expression (Greene et al., 2019). Ergovaline was a potent vasoconstrictor in the bovine umbilical and uterine arteries and reduces blood flow to developing placental tissues and fetuses (Klotz et al., 2015). Placental weight reduction was highly correlated with fetal birthweight and high exposure to EAs in ruminants can result in additional adverse effects such as hyperexcitability, hypermetria, and tremors (Britt et al., 2019; Klotz et al., 2015).

Pregnancy in humans

33. Data from trials on the use of EAs (ergometrine and methylergometrine) as uterotonic medication suggested that EAs may decrease mean blood loss from both mother and child by at least 500 mL and increase maternal haemoglobin levels in the blood. However, the results also suggested the treatment increased the incidence of adverse effects such as increased blood pressure and pain after birth (Liabsuetrakul et al., 2018).

34. A review of the Hungarian Case-Control Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies database, 1980-1986, suggested a possible link between the use of purified ergotamine and neural tube defects in humans. Ergotamine was used to treat acute migraine and a mean daily dose of 1.5 mg ergotamine during the 2nd month of pregnancy was associated with a higher risk for neural-tube defects. This was based only on three cases (Ács et al. 2006; Czeizel, 1989). There were two case reports of a possible association between the use of ergotamine during early pregnancy and the development of Möbius sequence in children (Smets et al., 2004; Graf and Shepard, 1997). Möbius sequence is a rare congenital disorder defined by the paralysis of the 6th and 7th cranial nerves in combination with various odontological, craniofacial, ophthalmological and orthopaedic conditions (Kjeldgaard Pedersen et al., 2017). Vascular disruption has been suggested as one possible explanation for the pathogenesis of Möbius sequence. However, Ács et al. (2006) found no evidence for an association between the use of ergotamine during pregnancy and Möbius sequence. Ergotamine has also been reported to cause vasospasm and a prolonged and marked increase in uterine tone (Smets et al., 2004; Graf and Shepard, 1997).

35. A single case report of a 36-year-old patient suggested that exposure to methylergonovine maleate (an EA derivate) at a critical stage of organogenesis was a possible cause of the development of sirenomelia. Sirenomelia is a rare and deadly condition characterized by fusion of the lower limbs, lower spinal column defects, severe malformations of the urogenital and lower GI tract, and an aberrant abdominal umbilical artery (Cozzolino et al., 2016).

Lactation in animals

36. Prolactin has important biological functions, including but not limited to lactation, reproduction, and metabolism and the inhibition of prolactin production by EAs has been seen in humans, laboratory animals, and livestock animals (Arroyo-Manzanares et al., 2017; Prendiville et al., 2000). Intraperitoneal injection of 1 mg ergocornine methane sulfonate in lactating rats temporarily inhibited milk production, the effect being prevented by treatment with prolactin (Zeilmakla and Carlsen, 1962). The potency of EAs to inhibit prolactin secretion in rats decreased in the following order: ergocornine > ergocryptine > dihydro-ergocryptine > dihydro-ergocornine > ergotamine > ergometrine (Griffith et al., 1978). Shaar and Clemens (1972) suggested that EAs directly affect the pituitary therefore preventing prolactin secretion, resulting in partial inhibition of lactation. Decreases in prolactin levels were observed in rats of both sexes with increasing amount of α-ergocryptine in the diet. In males, T4 was also significantly decreased and accompanied by a decrease in free thyroxine (FT4).

Lactation in humans

37. In a review of a randomised clinical trial to evaluate the effects of EAs on milk secretion postpartum, 30 women received an injection of 0.2 mg methylergobasine immediately after delivery followed by three tablets of 1 mg of ergotamine tartrate given daily (orally) for six days post-partum. The treatment had no significant effect on either the weight of the infant or the quantity of milk consumed (Jolivet et al., 1978). A study by Arroyo-Manzanares et al (2017) addressed the similarities of the actions of EAs to those of monoamine neurotransmitters and provided evidence that EAs have the ability to act on the secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), prolactin (PRL), LH and FSH.

Immune effects

38. Limited to no information was available on the effects of EA on the immune system. EFSA did not consider immunotoxicity in their assessment in 2012, while JECFA noted only that a high alkaloid content in the diet fed to rabbits for four weeks adversely affected the immune system, however no further information was available and potential immunotoxicity was not further discussed (JECFA, 2023).

39. A literature review was undertaken to establish whether any new information was available since the 2023 JECFA assessment, however no scientifically relevant information/data could be identified regarding the immunotoxicity of EAs.

Health-based guidance values

In this guide

In this guide40. EFSA (2012) considered the vasoconstrictive effect as the critical effect for EAs and derived a benchmark dose lower bound for a 10 % response (BMDL10) of 0.33 mg/kg bw per day, based on the finding of tail muscular atrophy in rats fed for 13 weeks with ergotamine. EFSA applied an overall uncertainty factor (UF) of 300, the default UF of 100 for intra- and interspecies differences and an additional UF of 3 to account for deficiencies in the database, to establish an acute reference dose (ARfD) of 1 μg/kg bw (rounded to one significant figure). In line with EFSA’s recommendations, an additional UF of 2 was applied to the establishment of the tolerable daily intake (TDI) for the extrapolation from a sub-chronic to a chronic study. Therefore, an overall UF of 600 was applied to the same BMDL10 of 0.33 mg/kg bw per day to establish a TDI of 0.6 μg/kg bw per day. EFSA concluded that the available data were not sufficient to determine the relative potencies of individual EAs, but the limited data available for some EAs showed no apparent differences in potencies.

41. In 2021, JEFCA, identified uterine contractions in humans during late pregnancy and postpartum, based on the pharmacological effect of ergotamine maleate, as the critical effect for the evaluation of EAs in the diet (JEFCA, 2021). JECFA established an ARfD based on the lowest oral therapeutic dose of 0.2 mg ergometrine maleate (equivalent to 2.5 μg/kg bw, expressed as ergometrine). An UF of 2 was applied for extrapolating a pharmacological lowest observed effect level (LOEL) to a no-observed effect level (NOEL) and an UF of 3.16 to account for possible interindividual toxicodynamic differences. Applying an overall UF of 6.3 an ARfD of 0.4 μg /kg bw ergometrine was established. JECFA also considered two 4-week studies on ergotamine tartrate and α-ergocryptine in rats and derived a reference point (BMDL10) of 1.3 mg/kg bw, based on muscular degeneration in the tail. However, JECFA considered the human pharmacological effect level of 2.5 μg/kg bw and resulting NOEL to provide a much more sensitive and relevant reference point than a downstream toxic effect in animals. A TDI of 1 μg/kg bw per day was initially established by selecting the lowest BMDL10 value of 0.6 mg/kg bw per day. However, JECFA concluded that a TDI should not be higher than the ARfD and hence decided to establish a group TDI for the sum of total EAs in the diet at the same value as the group ARfD of 0.4 μg/kg bw per day.

42. The COT considered that the JECFA evaluation provided the more conservative health based guidance value (HBGV), and, in addition, this was based on human endpoints and was more recent than the 2012 EFSA evaluation. The COT concluded they would align with JECFA and agreed on an ARfD of 0.4 μg/kg.

Sources of EAs exposure

In this guide

In this guide43. The European Union (EU) established maximum levels (ML) of ergot sclerotia and of EAs in Commission Regulation (EU) 2021/1399, effective as of January 2022. The ML of ergot sclerotia permitted in unprocessed cereals, with the exception of maize, rye and rice, is 0.2 g/kg. For unprocessed rye, the limit was 0.5 g/kg, further reduced to 0.2 g/kg in July 2024. For milled products derived from barley, wheat, spelt or oats with an ash content of less than 900 mg/100 g, a limit of 100 µg EAs/kg applies, which was further reduced to 50 µg/kg in July 2024. For the same types of grain products with a higher ash content or sold directly to the end consumer, the maximum level of EAs was set at 150 µg/kg. The maximum level of EAs in wheat gluten is 400 µg/kg. As an open pollination species, rye is generally more susceptible to infestation, which is reflected in a higher ML. Milled rye products are subject to an EAs limit of 500 µg/kg, which was further reduced to 250 µg/kg in July 2024. A ML of 20 µg/kg for EAs in grain-based food for infants and toddlers has also been introduced. The levels brought in by the EU for EAs as well as any subsequent changes to these limits do not apply in Great Britian (GB), however they do apply in Northern Ireland (NI).

44. EFSA’s estimated chronic dietary exposure to EAs in the adult population was between 0.007 and 0.08 μg/kg bw per day for average consumers and 0.014 and 0.19 μg/kg bw per day for high consumers. The estimated acute dietary exposure in the adult population ranged between 0.02 and 0.23 μg/kg bw per day for average consumers, and between 0.06 and 0.73 μg/kg bw per day for high consumers. The highest exposure (chronic and acute) was in countries with relatively high consumption of rye bread and rolls. Assessment of the dietary exposure to EAs in specific groups of the population indicated no significant differences between vegetarians and the general population. However, a slightly higher dietary exposure to EAs was noted in consumers of unprocessed grains compared to the general population (EFSA, 2012).

45. The German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) based their risk assessment of EAs on the consumption of rye flour contaminated with ergotamine and ergometrine. The BfR estimated that on average, ergotamine accounted for a maximum of 46 % of the total alkaloid content. The consumption of 250 g of the most contaminated rye flour would result in an intake of 834 µg ergotamine per day per person (BfR, 2004).

46. Caraballo et al. (2019) reported concentrations of EAs of up to 47 µg/kg in grains and grain-based composites. Despite effective cleaning procedures, surveys of Swiss, Canadian, Danish, and German cereals, cereal products and rye flours detected levels of EAs, with concentrations of up to 7.3 mg/kg (German rye flour) (Krska and Crews, 2008). Arroyo-Manzanares (2017) carried out an extensive survey on European products and tested 1,065 samples of cereals and cereal products (rye, wheat, and multigrain-based food that contain rye and wheat) intended for human consumption, as well as a number of animal feeds. In total, 59 % of samples tested positive for EAs, with EAs present in 84 % of rye food, 67 % of wheat food and 48 % of multigrain-based food. Levels overall ranged from 1 to 12,340 μg/kg, but while the highest frequencies of contamination were observed for food samples, feed samples accounted for the highest levels of ergot alkaloids. Storm et al. (2008) detected EAs in Danish rye flour samples with an average and maximum concentration of 46 μg/kg and 234 μg/kg, respectively. Crews et al. (2009) detected EAs in 25 of 28 samples, including all 11 types of rye crispbreads with concentration up to 340 μg/kg, while Müller et al. (2009) found EAs in 92 % of tested rye products with a maximum content of 740 μg/kg. Reinhold et al. (2011) tested 500 food samples from Germany, approximately 50 % of which were positive for EAs, with a highest concentration of 1,063 μg/kg. A more recent survey by Bryła et al. (2015) detected EAs in 83 % of tested rye grain, 94 % of rye flour, and 100 % of rye bran and flake samples. Ergocryptine, ergocristine, and ergotamine were the most common EAs detected in the majority of surveys and foods sampled. A study by Dusemund et al. (2006) concluded that ergometrine contributed 5 % of the total alkaloid content and that consumption of 250 g of the most contaminated rye flour would result in an intake of 91 µg ergometrine per day per person.

Exposure Assessment

In this guide

In this guide47. Estimated exposures to EAs were derived using data from the 2014 Total Diet Study (TDS)-Mycotoxin analysis (Stratton et al., 2017) and consumption data from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) for all groups and subpopulation groups (Bates et al., 2014, 2016, 2020; Roberts et al., 2018).

48. The TDS data was based on 28 food groups, which were further divided to produce 138 food categories. Total EAs and the epimers were determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) (Carbonell-Rozas et al., 2021). Ergocristine, ergotamine, ergocornine, ergosine, ergocryptine, ergometrine, ergocristinine, ergotaminine, ergocorninine, ergosinine, ergocryptinine and ergometrinine were the most frequent forms detected. More data on each specific subset are available in the TDS study report (Diet Study (TDS) – Mycotoxin Analysis Report, 2017).

49. In some food groups, some EAs were found only below the limit of quantification (LOQ). Where EAs were detected below the LOQ, the occurrence values were expressed as lower bound (LB) and upper bound (UB), where 0 is used as the analytical value for the LB value and the limit of detection/quantification is used as the analytical value for the UB value. Consequently, for some food groups, the results of the exposure assessment have been expressed as both LB and UB.

Overall exposure

In this guide

In this guide50. Mean and 97.5th percentile estimated exposure to EAs from the individual food groups for women of child-bearing age (16- 49 years) can be found in Table 1 (acute) and Table 2 (chronic).

Table 1: Estimates acute exposure to ergot alkaloids in women of childbearing age; food groups not containing EAs have been excluded.

|

Food groups |

Exposure (ng/kg bw) LB – UB Mean |

Exposure (ng/kg bw) LB – UB P97.5 |

|

White sliced bread |

9.2-9.3 |

41.0 |

|

White unsliced bread |

6.0-6.1 |

34.0-35.0 |

|

Brown bread |

2.3 |

33.0 |

|

Wholemeal and granary bread |

24.0 |

91.0 |

|

Other bread |

15.0 |

68.0 |

|

Misc cereals Flour |

1.5-1.7 |

12.0-13.0 |

|

Misc cereals Buns cakes and pastries |

1.9-2.7 |

9.4-13.0 |

|

Misc cereals Savoury biscuits |

0.9 |

7.6-7.7 |

|

Misc cereals Sweet biscuits |

1.5-1.6 |

8.4-9.0 |

|

Misc cereals Chocolate biscuits |

0.6 |

5.4-5.8 |

|

Misc cereals Breakfast cereals |

3.0 |

18.3-18.4 |

|

Misc cereals Rice |

0-6.2 |

0-25.0 |

|

Misc cereals Other cereal products |

1.0-1.7 |

8.8-15.0 |

|

Misc cereals Pasta |

2.2-6.5 |

8.9-27.0 |

|

Misc cereals Pizza |

7.2-7.5 |

54.0-56.0 |

|

Total |

52.0-57.0 |

120.0-130.0 |

LB= lower bound; UB= upper bound.

Misc = miscellaneous.

Where rounding produced the same value for the upper and lower bound, single figures have been used within the table.

Estimates of total exposure (mean, P97.5) were determined from an overall distribution of the consumption of any combination of the food categories included in the assessment, rather than by summation of the individual mean or 97.5th percentile consumption values for each of the food categories.

Table 2: Estimated chronic exposure to ergot alkaloids in women of childbearing age; food groups not containing EAs have been excluded.

|

Food groups |

Exposure (ng/kg bw) LB – UB Mean |

Exposure (ng/kg bw) LB – UB P97.5 |

|

White sliced bread |

4.0-4.1 |

21.4-21.5 |

|

White unsliced bread |

2.1 |

12.8-12.9 |

|

Brown bread |

0.8 |

10.0 |

|

Wholemeal and granary bread |

0.011 |

52.0 |

|

Other bread |

0.0055 |

29.0 |

|

Misc cereals Flour |

0.6 |

4.7-5.2 |

|

Misc cereals Buns cakes and pastries |

0.7-0.9 |

3.8-5.2 |

|

Misc cereals Savoury biscuits |

0.3 |

3.1 |

|

Misc cereals Sweet biscuits |

0.6 |

3.6-3.9 |

|

Misc cereals Chocolate biscuits |

0.2 |

1.8-1.9 |

|

Misc cereals Breakfast cereals |

1.9 |

8.9-9.0 |

|

Misc cereals Rice |

0-2.4 |

0-12 |

|

Misc cereals Other cereal products |

0.3-0.5 |

2.8-4.8 |

|

Misc cereals Pasta |

0.7-2.1 |

3.5-10.0 |

|

Misc cereals Pizza |

1.9-2.0 |

15.0 |

|

Total |

31.0-35.0 |

72.0-80.0 |

LB= lower bound; UB= upper bound.

Misc = miscellaneous.

Where rounding produced the same value for the upper and lower bound, single figures have been used within the table.

Estimates of total exposure (mean, P97.5) were determined from an overall distribution of the consumption of any combination of the food categories included in the assessment, rather than by summation of the individual mean or 97.5th percentile consumption values for each of the food categories.

51. The mean and 97.5th percentile total estimated acute exposure (exposure from all products) ranges from 52 - 57 ng/kg bw and 120 - 130 ng/kg bw respectively. The mean and 97.5th percentile total estimated chronic exposure ranges from 31 - 35 ng/kg bw and 72 - 80 ng/kg bw, respectively.

52. The food groups contributing most to EAs exposure were a) wholemeal and granary bread (acute exposure 24 - 91 ng/kg bw, chronic exposure 0.011 - 52 ng/kg bw), b) white sliced bread (acute exposure 9.2 - 41 ng/kg bw, chronic exposure 4 - 21.5 ng/kg bw), and c) other bread (acute exposure 15 - 68 ng/kg bw, chronic exposure 0.0055 - 29 ng/kg bw).

Exposures in subpopulation groups

Vegans and Vegetarians

53. The numbers of vegans (n=10) and vegetarians (n=112) among the total number of consumers (n= 2556) were relatively small.

54. For vegans (n=10) the LB and UB mean and 97.5th percentile acute exposures were 64 – 70 ng/kg bw and 127 – 130 ng/kg bw, respectively. For vegetarians (n=112) the LB and UB mean and 97.5th percentile exposures were 61 – 67 ng/kg bw and 135 – 140 ng/kg bw, respectively.

55. For vegans (n=10) the LB and UB mean and 97.5th percentile chronic exposures were 44 – 49 ng/kg bw and 84 – 87 ng/kg bw, respectively. For vegetarians (n=112) the LB and UB mean and 97.5th percentile exposures were 38 – 43 ng/kg bw and 78 – 92 ng/kg bw, respectively.

Ethnicity

56. The numbers of Asian or Asian British women of childbearing age (n=135) and Black or Black British women of childbearing age (n=82) were relatively small compared to White women of childbearing age (n=2234).

57. The LB and UB mean and 97.5th percentile acute exposures were 57.8 - 68 ng/kg bw and 110 - 130 ng/kg bw for Asian women, respectively. The LB and UB mean and 97.5th percentile acute exposures were 47 - 55 ng/kg bw and 100 - 110 ng/kg bw for Black women, respectively. For White women the LB and UB mean and 97.5th percentile exposures were 52 - 56 ng/kg bw and 120 - 130 ng/kg bw, respectively.

58. The LB and UB mean and 97.5th percentile chronic exposures were 34 - 46 ng/kg bw and 71 - 97 ng/kg bw for Asian women, respectively. The LB and UB mean and 97.5th percentile exposures were 27 - 33 ng/kg bw and 73 - 85 ng/kg bw for Black women, respectively. For White women the LB and UB mean and 97.5th percentile exposures were 30 - 34 ng/kg bw and 73 - 79 ng/kg bw, respectively.

Risk Characterisation

In this guide

In this guide59. EAs can act as both agonists and antagonists at noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin receptors and produce peripheral effects (including uterotonic action and vasoconstriction) and CNS effects (including induction of hypothermia and emesis, and effects on the secretion of pituitary hormones).

60. EAs are not considered carcinogenic but have not been assessed by the IARC. The data on the genotoxic and mutagenic effects of EAs are somewhat limited and at times contradictory. EFSA (2012) considered the available genotoxicity studies to be insufficient, with the exception of those for ergotamine, which indicated that it did not cause bacterial or mammalian cell mutation. JECFA (2023) concluded that overall, naturally occurring EAs do not raise concerns for genotoxicity. The COT is of a similar view.

61. Exposure to EAs has been associate with pregnancy hindrance by interfering with egg implantation and embryotoxicity in rodents, negative effects on maternal blood supply to the placenta in ewes and possibly sirenomelia associated with in utero exposure in humans. EAs can negatively affect lactation due to their hormone mimicking activity, in particular on LH/FSH balance and prolactin levels (Della-Giustina eta al., 2003).

62. EFSA (2012) established an ARfD of 1 μg/kg bw and a TDI of 0.6 μg/kg bw per day for EAs. JECFA established a group TDI for the sum of total EAs in the diet at the same value as the group ARfD of 0.4 μg/kg bw. The COT considered the JECFA ARfD and TDI of 0.4 μg/kg bw more appropriate due to the more recent evaluation and its inclusion of human endpoints.

63. Using mycotoxin data from the TDS, mean and 97.5th percentile total estimated acute exposures were 52 - 57 ng/kg bw and 120 - 130 ng/kg bw respectively. Mean and 97.5th percentile total estimated chronic exposures were 31 - 35 ng/kg bw and 72 - 80 ng/kg bw respectively. All estimated exposures are below the respective ARfD and TDI established by JECFA and are therefore not a toxicological concern. The exposures here were also below any therapeutic doses that have shown adverse effects.

64. The food groups contributing most to the overall exposures were wholemeal and granary bread, white sliced bread and other bread. However, it should be noted that the dietary exposure estimates were based on a limited number of food groups and that data from ready-to-eat foods were scarce. A contribution to overall EAs exposure from other foods cannot therefore be excluded.

65. Total exposure was estimated by summing food consumption for each individual in the food survey and deriving distributions of consumption. The total mean, and 97.5th percentile were determined from an overall distribution of the consumption of any combination of the food categories included in the assessment, rather than by summation of the individual mean or 97.5th percentile consumption values for each of the food categories. For food groups with non detects, exposure was calculated using the limit of detection (LOD)/LOQ as the upper bound and 0 as the lower bound occurrence value. This approach may produce a more conservative exposure estimate and increase the margin of safety (MoS).

66. The current assessment was based on consumption data from the NDNS for women of childbearing age and therefore may not be fully representative of maternal diet. The relatively small data set and limited number of EAs evaluated further add a level of uncertainty to the results.

Conclusions

In this guide

In this guide67. Using occurrence data from the 2011 TDS for EAs and consumption data from the NDNS for woman of childbearing age, all estimated mean and 97.5th percentile exposures are below the respective ARfD and TDI of 0.4 μg/kg bw and are therefore not of toxicological concern. These exposures are also below any therapeutic dose of natural or synthetic EAs reported to have adverse effects.

68. The assessment was based on a relatively small sample size (food groups, EAs tested), which reduced confidence in the estimates. In addition, the consumption data may not be fully representative of the maternal diet as the data were for women of childbearing age. However, estimation of total exposure using the 97.5th percentile for all food groups was conservative, as it assumed high consumption across all food groups. On balance, it is concluded that the margin of safety is sufficient to conclude that dietary exposure to EAs is not of toxicological concern in pregnant women.

69. The COT noted that environmental factors such as climate change may affect exposure to EAs, with wetter weather resulting in an increase of EAs in foods, e.g. rye. However, this is part of a wider issue on climate change and a potential increase in food borne risks and would not be limited to just EAs.

Abbreviations

In this guide

In this guide|

ACTH |

Adrenocorticotropic hormone |

|

ARfD |

Acute reference dose |

|

BfR |

Bundesinstitut fuer Risikobewertung/German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment |

|

BMDL |

Benchmark Dose Lower Confidence Limit |

|

CHO |

Chinese hamster ovary |

|

CLoA |

Clavine oxidase |

|

CNS |

Central nervous system |

|

COT |

Committee on the Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment |

|

EAs |

Ergot alkaloids |

|

EFSA |

European Food Safety Authority |

|

Et |

Ergotamine tartrate |

|

EU |

European Union |

|

FAO |

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

|

FSH |

Follicle-stimulating hormone |

|

GB |

Great Britian |

|

GI tract |

Gastrointestinal tract |

|

HBGV |

Health based guidance value |

|

5-HT |

5-hydroxytryptamine |

|

IARC |

International Agency for Research on Cancer |

|

i.v. |

Intravenous |

|

JECFA |

Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives |

|

LA |

Lysergic acid |

|

LB |

Lower bound |

|

LC/MS/MS |

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

|

LD |

Lethal dose |

|

LH |

Luteinizing hormone |

|

LO(A)EL |

Lowest observed (adverse) effect level |

|

LOD |

Limit of detection |

|

LOQ |

Limit of quantification |

|

LSD |

Lysergic acid diethylamide |

|

mg/kg |

Milligram per kilogram |

|

miRNA |

micro ribonucleic acid |

|

Misc |

Miscellaneous |

|

ML |

Maximum levels |

|

MoS |

Margin of Safety |

|

NDNS |

National Diet and Nutrition Survey |

|

ng/g |

Nanogram per gram |

|

NI |

Northern Ireland |

|

NO(A)EL |

No observed adverse effect level |

|

PRL |

Prolactin |

|

SACN |

Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition |

|

s.c. |

Subcutaneous |

|

SCE |

Sister chromatid exchange |

|

St |

Salmonella typhimurium |

|

(F)T4 |

(Free) thyroxine |

|

TDI |

Tolerable daily intake |

|

TDS |

Total Diet Study |

|

TSH |

Thyroid-stimulating hormone |

|

UB |

Upper bound |

|

UF |

Uncertainty factor |

|

WHO |

World Health Organisation |

|

μg |

μg = microgram |

|

μg/g |

microgram per gram |

|

μg/kg |

microgram per kilogram |

|

μg/L |

microgram per litre |

References

In this guide

In this guideÁcs N, Bánhidy F, Puhó E and Czeizel AE (2006). A possible dose-dependent teratogenic effect of ergotamine. Reprod Toxicol, 22(3): 551-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.03.002

Aellig WH and Nüesch E (1977). Comparative pharmacokinetic investigations with tritium-labeled ergot alkaloids after oral and intravenous administration man. Int J Clin Pharmacol Biopharm. 15(3):106-12. PMID: 403149. Comparative pharmacokinetic investigations with tritium-labeled ergot alkaloids after oral and intravenous administration man - PubMed

Arroyo-Manzanares N, Gámiz-Gracia L, García-Campaña AM, Di Mavungu JD, De Saeger S (2017). Ergot Alkaloids: Chemistry, Biosynthesis, Bioactivity, and Methods of Analysis. Fungal Metabolites 887-929 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25001-4_

Agriopoulou S (2021). Ergot Alkaloids Mycotoxins in Cereals and Cereal-Derived Food Products: Characteristics, Toxicity, Prevalence, and Control Strategies. Agronomy. 11. 931. Ergot Alkaloids Mycotoxins in Cereals and Cereal-Derived Food Products: Characteristics, Toxicity, Prevalence, and Control Strategies

Bates B, Lennox A, Prentice A, Bates C, Page P, Nicholson S, Swan G (2014). National Diet and Nutrition Survey Results from Years 1, 2, 3 and 4 (combined) of the Rolling Programme (2008/2009 – 2011/2012) National Diet and Nutrition Survey Results from Years 1, 2, 3 and 4 (combined) of the Rolling Programme (2008/2009 – 2011/2012

Bates B, Cox L, Nicholson S, Page P, Prentice A, Steer T, Swan G (2016). National Diet and Nutrition Survey Results from Years 5 and 6 (combined) of the Rolling Programme (2012/2013 – 2013/2014) National Diet and Nutrition Survey Results from Years 5 and 6 (combined) of the Rolling Programme (2012/2013 – 2013/2014)

Bernard N, Jantzem H, Becker M, Pecriaux C, Bénard-Laribière A, Montastruc JL, Descotes J, Vial T (2015). Severe adverse effects of bromocriptine in lactation inhibition: a pharmacovigilance survey. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 122(9): 1244-51. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13352

Bogun N, Mathies R, Baesecke J (2011). Angiospastic occlusion of the superficial femoral artery by chronic ergotamine intake. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift, 136(1-2): 23-6. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1269435

Bryła M, Szymczyk K, Jędrzejczak R, Roszko M (2015). Application of liquid chromatography/ ion trap mass spectrometry technique to determine ergot alkaloids in grain products. Food Technol Biotechnol 53:18–28. https://doi.org/10.17113/ftb.53.01.15.3770

Britt JL, Greene MA, Bridges Jr WC, Klotz JL, Aiken GE, Andrae JG, Pratt SL, Long NM, Schrick FN, Strickland JR, Wilbanks SA, Miller Jr MF, Koch BM, Duckett SK (2019). Ergot alkaloid exposure during gestation alters. I. Maternal characteristics and placental development of pregnant ewes. Journal of Animal Science, 97(4):1874–90. https://doi.org/10.1093%2Fjas%2Fskz068

Bryła M, Szymczyk K, Jędrzejczak R, Roszko M (2015). Application of liquid chromatography/ ion trap mass spectrometry technique to determine ergot alkaloids in grain products. Food Technol Biotechnol 53:18–28. https://doi.org/10.17113/ftb.53.01.15.3770

Caraballo D, Toloso J, Ferrer E, Berrada H (2019). Dietary exposure assessment to mycotoxins through total diet studies. A review. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 128: 8-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2019.03.033

Carbonell-Rozas L, Gamiz-Gracia L, Lara FJ, Garcia-Campana AM (2021). Determination of the main ergot alkaloids and their epimers in oat-based functional foods by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Molecules, 26(12): 3717. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26123717

Cassady JM, Li GS, Spitzner EB, Floss H, Clemens JA (1974). Ergot alkaloids. Ergolines and related compounds as inhibitors of prolactin release. J Med Chem. (3):300-7. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm00249a009

Cozzolino M, Riviello C, Fichtel G, Di Tommaso M (2016). Brief Report Exposure to Methylergonovine Maleate as a Cause of Sirenomelia. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 106(7): 643-7. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdra.23503

Commission Regulation (EU) 2021/1399 of 24 August 2021 amending Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 as regards maximum levels of ergot sclerotia and ergot alkaloids in certain foodstuffs (Text with EEA relevance). Regulation - 2021/1399 - EN - EUR-Lex

COT (2017). Review of potential risks from mycotoxins in the diet of infants aged 0 to 12 months and children aged 1 to 5 years. tox2017-30_0.pdf

Crews C, Anderson WAC, Rees G, Krska R (2009). Ergot alkaloids in some rye-based UK cereal products. Food Addit Contam Part B Surveill 2:79–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/02652030903042509

Czeizel A (1989). Teratogenicity of ergotamine. J Med Genet 26(1):69-70

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jmg.26.1.69-a

Della-Giustina K and Chow G (2003). Medications in pregnancy and lactation. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America, 21(3): 585-613.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0733-8627(03)00037-3

De Ruyck K, De Boevre M, Huybrechts I, De Saeger S (2015). Dietary mycotoxins, co-exposure, and carcinogenesis in humans: Short review. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research, 766: 32-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrrev.2015.07.003

DH (2013). Diet and Nutrition Survey of Infants and Young Children (DNSIYC), 2011.

Diet and nutrition survey of infants and young children, 2011 - GOV.UK

Dighe R and Vaidya VG (1988). Induction of sister chromatid exchanges by ergot compounds in Chinese hamster ovary cells in vitro. Teratog. Carcinog. Mutagen. 8, 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/tcm.1770080306

Duckett SK, Andrae JG, Prat SL (2014). Exposure to Ergot alkaloids during gestation reduces fetal growth in sheep. Frontiers in Chemistry, 21: 2:68. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2014.00068

Dusemund B, Altmann H-J and Lampen A, (2006). II. Toxikologische Bewertung Mutterkornalkaloidkontaminierter Roggenmehle. Journal of Consumer Protection and Food Safety, 1, 150-152. „ „Mutterkornalkaloide in Lebensmitteln“ | Journal of Consumer Protection and Food Safety | Springer Nature Link

Eckert H, Kiechel JR, Rosenthaler J, Schmidt R, Schreier E (1978). Biopharmaceutical Aspects. In: Berde, B., Schild, H.O. (eds) Ergot Alkaloids and Related Compounds. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology / Handbuch der experimentellen Pharmakologie, vol 49. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-66775-6_11

EFSA (2005). Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Contaminants in Food Chain on a request from the Commission related to ergot as undesirable substance in animal feed. EFSA Journal (2005)225, 1 – 27. Opinion of the Scientific Panel on contaminants in the food chain [CONTAM] related to ergot as undesirable substance in animal feed - - 2005 - EFSA Journal - Wiley Online Library

EFSA (2012). Scientific Opinion on Ergot alkaloids in food and feed. EFSA Journal, 10(7): 2798. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2798

Fayrer-Hosken R., Stanley A., Hill N., Heusner G., Christian M., De La Fuente R., Baumann C., Jones L. (2012). Effect of feeding fescue seed containing ergot alkaloid toxins on stallion spermatogenesis and sperm cells. Reprod Domest Anim 47(6): 1017-26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0531.2012.02008.x

Fayrer-Hosken RA, Hill NS, Heusner GL, Traylor-Wiggins W, Turner K (2013). The effects of ergot alkaloids on the breeding stallion reproductive system. Equine Vet J Suppl 12 (45):44-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/evj.12164

Fitzgerald P and Dinan TG (2008). Prolactin and dopamine: what is the connection? A review article. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 22(2 Suppl), 12-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216307087148

Fröhlich G, Kaplan V, Amann-Vesti B (2010). Holy fire in an HIV-positive man: a case of 21st century ergotism. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 182 (4): 378-80. https://doi.org/10.1503%2Fcmaj.091362

FSA (2014). Monitoring the Presence of Ergot Alkaloids in Cereals and a Study of a Possible Relationship between Occurrence of Sclerotia Content and Levels of Ergot Alkaloids. Monitoring the presence of ergot alkaloids in cereals | Food Standards Agency

Garcia GD, Goff Jr JM, Hadro NC, I-Donnell SD, Greatorex PS (2000). Chronic ergot toxicity: A rare cause of lower extremity ischemia. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 31(6): 1245-7. https://doi.org/10.1067/mva.2000.105668

Gerhards N, Neubauer L, Tudzynski P, Li SM (2014). Biosynthetic Pathways of Ergot Alkaloids. Toxins, 6(12):3281-95. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Ftoxins6123281

Graf WD and Shepard TH (1997). Uterine contraction in the development of Möbius syndrome. Journal of Child Neurology,12(3): 225-7. https://doi.org/10.1177/088307389701200315

Greene MA, Britt JL, Powell RP, Feltus FA, Bridges WC, Bruce T, Klotz JL, Miller MF, Duckett SK (2019). Ergot alkaloid exposure during gestation alters: 3. Fetal growth, muscle fiber development, and miRNA transcriptome. Journal of Animal Science, 97(7):3153-68. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skz153

Griffith RW, Grauwiler J, Hodel Ch, Leist KH, Matter B, (1978). In: Berde, B., Schild, H.O. (Eds.), Toxicologic Considerations. Ergot Alkaloids and Related Compounds. Springer Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 805–851, abstract only. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-66775-6

Guggisberg H (1954). Changes in the therapeutic use of ergot. Ther Umsch. 11(4):77-9.

Haarmann T, Ortel I, Tudzynski P, Keller U (2006). Identification of the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase that bridges the clavine and ergoline alkaloid pathways. ChemBioChem – Chemistry Europe. 7(4):645-52. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.200500487

Hardman J, Limbird L, Gilman A (2001). The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. Goodman & Gilman’s 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. Anesthesia & Analgesia

Harleman J, Hargreaves A, Andersson H, Kirk S (2012). A Review of the Incidence and Coincidence of Uterine and Mammary Tumors in Wistar and Sprague-Dawley Rats Based on the RITA Database and the Role of Prolactin. Toxicologic Pathology. 40(6):926-930. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192623312444621

Janssen GB, Beems RB, Elvers LH, Speijers GJ (2000). Subacute toxicity of α-ergocryptine in Sprague-Dawley rats. 2: metabolic and hormonal changes. Food Chem Toxicol. 38:689–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-6915(00)00055-7

JECFA (2021). Safety evaluation of certain food additives and contaminants. Summary report of the ninety-first meeting. Evaluation of certain food additives and contaminants: ninety-first report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives

JECFA (2023). Safety evaluation of certain contaminants in food: prepared by the ninety-first meeting of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA). Safety evaluation of certain contaminants in food: prepared by the ninety-first meeting of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA)

Jolivet A, Robyn C, Huraux-Rendu C, Gautray JP (1978). Effect of ergot alkaloid derivatives on milk secretion in the immediate postpartum period. Journal de Gynecologie, Obstetrique et Biologie de la Reproduction 7(1):129-134.

Kjeldgaard Pedersen L, Rikke Damkjær Maimburg R, Hertz JM, Gjørup H, Klit Pedersen T, Møller-Madsen B, Rosendahl Østergaard J (2017). Moebius sequence – a multidisciplinary clinical approach. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 12(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-016-0559-z

Klotz J (2015). Activities and Effects of Ergot Alkaloids on Livestock Physiology and Production. Toxins (Basel) 7(8), 2801-2821. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins7082801

Klotz JL, Britt JL, Miller MF, Snider MA, Aiken GE, Long NM, Pratt SL, Andrae GJ, Duckett SK (2019). Ergot alkaloid exposure during gestation alters: II. Uterine and umbilical artery vasoactivity. Journal of Animal Science, 97(4): 1891-1902. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skz069

Korn AK, Gross M, Usleber E Thom N, Köhler K, Erhardt G (2014). Dietary ergot alkaloids as a possible cause of tail necrosis in rabbits. Mycotoxin Residues, 30(4):241–50. https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs12550-014-0208-0

Krska R and Crews C (2008). Significance, chemistry and determination of ergot alkaloids: a review. Food Additives and Contaminants: Part A, chemistry, analysis, control, exposure and risk assessment, 25(6):722-31. https://doi.org/10.1080/02652030701765756

Liabsuetrakul T, Choobun T, Peeyananjarassri K, Monir Islam Q (2018). Prophylactic use of ergot alkaloids in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7;6(6):CD005456. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005456.pub3

Lieberman AN and Goldstein M (1985). Bromocriptine in Parkinson disease. Pharmacological Review. 37(2) 217-27. Bromocriptine in Parkinson disease - PubMed

Little PJ, Jennings GL, Skews H, Bobik A (1982). Bioavailability of dihydroergotamine in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 13(6):785-90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.1982.tb01866.x

MacLeod RM and Lehmeyer J (1973). Suppression of Pituitary Tumor Growth and Function by Ergot Alkaloids. Cancer Research 33, 849-855.

Mrusek M, Seo E-J, Greten HJ, Simon M, Efferth T (2015). Identification of cellular and molecular factors determining the response of cancer cells to six ergot alkaloids. Invest New Drugs. 33(1):32-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10637-014-0168-4

Mulac D and Humpf HU (2011). Cytotoxicity and accumulation of ergot alkaloids in human primary cells. Toxicology, 282(3):112–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2011.01.019

Müller C, Kemmlein S, Klaffke H, Krauthause W, Preiss-Weigert A, Wittkowski R (2009). A basic tool for risk assessment: a new method for the analysis of ergot alkaloids in rye and selected rye products. Mol Nutr Food Res 53:500–507 https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.200800091

Olver IN, Jennings GL, Bobik A, Esler M (1980). Low bioavailability as a cause of apparent failure of dihydroergotamine in orthostatic hypotension. British Medical Journal. 281(6235):275-276. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.281.6235.275-a

Orton DA and Richardson RJ (1982). Ergotamine absorption and toxicity. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 58(675): 6-11. https://doi.org/10.1136%2Fpgmj.58.675.6

Page R, Lester T, Rorie R, Rosenkrans Jr C (2019). Ergot Alkaloid Effects on Bovine Sperm Motility In Vitro. Advance in Reproductive Science, 7(1): 7-15. https://doi.org/10.4236/arsci.2019.71002

Poole R and Poole DH (2019). Impact of Ergot Alkaloids on Female Reproduction in Domestic Livestock Species. Toxins, 11(6): 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11060364

Prendiville WJ, Elbourne D, McDonals S (2000). Active versus expectant management in the third stage of labor. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, 3. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd000007

Perrin VL (1985). Clinical pharmacokinetics of ergotamine in migraine and cluster headache. Clinical Pharmacokinetics 10(4): 334–52. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-198510040-00004

Reinhold L, Reinhardt K (2011). Mycotoxins in foods in Lower Saxony (Germany): results of official control analyses performed in 2009. Mycotoxin Res 27:137–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12550-011-0086-7

Roberts C, Steer, T, Maplethorpe N, Cox L, Meadows S, Page P, Nicholson S, Swan G (2018). National Diet and Nutrition Survey Results from Years 7 and 8 (combined) of the Rolling Programme (2014/2015 – 2015/2016) National Diet and Nutrition Survey

Roberts G and Rand MJ (1977). Chromosomal damage induced by some ergot derivatives in vitro. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 48 (2):205-214. https://doi.org/10.1016/0027-5107(77)90162-2

Schardl CL, Panaccione DG and Tudzynski P, 2006. Ergot Alkaloids - Biology and Molecular Biology. In: The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology. Vol. 63. Ed Cordell GA. Academic Press, San Diego, USA, 45-86.

Schiff PL (2006). Ergot and its alkaloids. Am J Pharm Educ 70(5):98. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj700598

Seifried, H.E., Seifried, R.M., Clarke, J.J., Junghans, T.B., San, R.H.C. (2006). A compilation of two decades of mutagenicity test results with the Ames Salmonella typhimurium and L5178Y mouse lymphoma cell mutation assays. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 19, 627–644. https://doi.org/10.1021/tx0503552

Shaar CJ and Clemens JA (1972). Inhibition of lactation and prolactin secretion in rats by ergot alkaloid. Endocrinology. 90:285–88 [abstract only]. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-90-1-285

Silberstein SD and McCrory DC (2003). Ergotamine and dihydroergotamine: history, pharmacology, and efficacy. Headache, 43(2): 144-66. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03034.x

Smets K, Zecic A, Willems J (2004). Ergotamine as a possible cause of Möbius sequence: additional clinical observation. Journal of Child Neurology, 19(5): 398. https://doi.org/10.1177/088307380401900518

Storm ID, Have Rasmussen P, Strobel BW, Hansen HCB (2008). Ergot alkaloids in rye flour determined by solid-phase cation-exchange and high-pressure liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. Food Addit Contam 25:338–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/02652030701551792

Stratton J, Anderson S, Leon I, Hepworth P, Chapman S, Christy J, Jardine S, Philips D, Setter R, Clough J, MacDonals S (2017). Diet Study (TDS) – Mycotoxin Analysis. Final Report, FS102081. Fera Science Ltd, York (UK). Diet Study (TDS) – Mycotoxin Analysis Report, 2017 - Search

Tasker NR and Wipf P (2021). Biosynthesis, total synthesis, and biological profiles of Ergot alkaloids. Alkaloids Chemical Biology, 85:1-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.alkal.2020.08.001

Tfelt-Hansen, P., Saxena, P.R., Dahlof, C., Pascual, J., Lainez, M., Henry, P.,Diener, H.,Schoenen, J., Ferrari, M.D., Goadsby, P.J., (2000). Ergotamine in the acute treatment of migraine: a review and European consensus. Brain 123 (Pt 1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/123.1.9

Valente Eel, Klotz JL, Ahn G, McLeod KR, Herzing HM, King M, Harmon DL (2020). Ergot alkaloids reduce circulating serotonin in the bovine. Journal of Animal Science, 98(12). https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skaa362

Wyss PA, Rosenthaler J, Nüesch E, Aellig WH (1991). Pharmacokinetic investigation of oral and IV dihydroergotamine in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 41, 597–602. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00314992

Young CA, Schardl CL, Panaccione DG, Florea S, Takach JE, Charlton ND, Moore N, Webb JS, Jaromczyk J (2015). Genetics, Genomics and Evolution of Ergot Alkaloid Diversity. Toxins (Basel). Apr 14;7(4):1273–1302. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins7041273

Zeilmaker GH and Carlsen RA (1962). Experimental studies on the effect of ergocornine methanesulphonate on the luteotrophic function of the rat pituitary gland. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 41:321-35. https://doi.org/10.1530/acta.0.0410321

Appendix A

In this guide

In this guideLiterature Search Terms for Ergot Alkaloids (January 2022 - June 2022)

|

acute toxicity |

|

chronic toxicity |

|

reproductive toxicity |

|

biomarkers (exposure/ toxicity) |

|

maternal health |

|

preconception |

|

conception |

|

pregnancy |

|

post-natal |

|

lactation |

|

fetus/ foetus/ fetal /foetal |

|

placenta |

|

pre-term |

|

preeclampsia |

|

cancer/ carcinogen(icity) |

|

teratogen(icity) |

|

absorption |

|

distribution |

|

metabolism |

Appendix B

In this guide

In this guideFood groups analysed in the TDS for EAs.

Table 5: List of all food groups analysed for ergot alkaloids (EAs).

Bread

|

Category |

Occurrence data total EAs (µg/kg) |

|

White sliced bread |

14.08 |

|

White unsliced bread |

11.88 |

|

Brown bread |

27.29 |

|

Wholemeal and granary bread |

33.69 |

|

Other bread |

23.29 |

Miscellaneous cereals

|

Category |

Occurrence data total EAs (µg/kg) |

|

Flour |

19.46 |

|

Buns cakes and pastries |

8.25 |

|

Savoury biscuits |

2.23 |

|

Sweet biscuits |

9.34 |

|

Chocolate biscuits |

4.90 |

|

Breakfast cereals |

3.07 |

|

Rice |

7.08 |

|

Other cereal products |

0.00 |

|

Pasta |

0.64 |

|

Pizza |

0.00 |

|

Group sample |

6.94 |

Non-alcoholic beverages (With bottles water)

|

Category |

Occurrence data total EAs (µg/kg) |

|

Branded food drinks |

4.30 |

|

Alternatives to milk |

0.00 |

Alcoholic drinks

|

Category |

Occurrence data total EAs (µg/kg) |

|

Beer |

0.00 |

|

Cider |

0.00 |

Snacks

|

Category |

Occurrence data total EAs (µg/kg) |

|

Other snacks (not potato based) |

3.65 |

Sandwiches

|

Category |

Occurrence data total EAs (µg/kg) |

|

Group sample |

NA |