Introduction

In this guide

In this guideOn this page

Skip the menu of subheadings on this page.This is a draft statement for discussion. It does not reflect the final views of the Committee and should not be cited.

Type A trichothecenes

6. T-2 and HT-2 are type A trichothecenes which are produced by a variety of Fusarium and other fungal species. Fusarium species grow and invade crops and produce T-2 and HT-2 under cool, moist conditions prior to harvest. They are found predominantly in cereal grains, and in particular oat grain, barley grain and wheat grain and products thereof, i.e. foods prepared from recipes containing cereal grains. (JECFA, 2016).

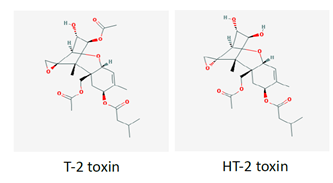

7. The chemical structures of T-2 and HT-2 are shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Chemical structures of T-2 and HT-2 (PubChem, 2025).

Occurrence data

8. As part of this assessment, occurrence data on T-2 and HT-2 (only) in food were acquired through a nationwide call for evidence (FSA, 2023). This call was issued by the FSA and FSS in July 2023 and officially closed in October 2023. However, the FSA and FSS continued to receive data up until February 2024. The data call focussed on cereal grains both pre- and post- cleaning/dehulling, and finished products including, where possible, data that spanned multiple years to reflect any annual variability of T-2 and HT-2 levels. The data received (n= >8000) covered the UK harvest seasons from 2004 to 2023. Sampling data for RTE food products were also submitted for 2013 (n=60), 2014 (n=60) and 2024 (n=90).

9. The FSA and FSS received occurrence data on T-2 and HT-2, only, either as the sum of T-2 and HT-2 or as the individual mycotoxins. The level of detail provided by the respondents and the format varied, but the data included occurrence levels in processed and unprocessed cereal grains, cereal products and a small number of RTE foods. The occurrence data submitted to the FSA and FSS were predominantly on unprocessed/raw materials, which were yet to undergo any cleaning. Occurrence data on grains submitted by industry as ‘already processed’ refers to grains that have been dehulled and cleaned, but remain as a commodity, that is they have not been incorporated in any RTE foods. Submitted data on RTE foods included biscuits, rusks and cookies, extruded cereal seed or root-based products, cereal bars, infant formula milk-based powder, oat porridge, muesli, mixed breakfast cereals, bread and rolls.

10. The data were collated, cleaned and assured by the FSA. The quality assurance (QA) methodology aligned with the main principles outlined in the Treasury Guidance (Aqua Book; UK HM Treasury, 2015) and the guidelines in the Government Data Quality Framework (UK Government Data Quality Hub, 2020) on data quality rules.

11. Prior to the data cleaning, a verification exercise was undertaken by the FSA to account for missing limit of quantification (LOQ) and/or limit of detection (LOD) values and sample type categorisation. For these amendments, assumptions were made based on the descriptors and values included by the submitters, such as the descriptors provided for commodity types based on the sample identification codes. The following criteria were applied to include data without compromising scientific integrity. Data were included when all of the following criteria were satisfied:

- Datapoints with reported LOQ > 0.

- Datapoints where the FoodEx (EFSA, 2025) code could be defined.

- Sample codes referred to products destined for human consumption (not feed).

12. To estimate the median lower bound (LB) sum of T-2 and HT-2, values that were at or below the LOQ were assumed to be zero. To estimate the median upper bound (UB) occurrence levels, values that were at or below the LOQ were assumed to be at the LOQ; values above the LOQ were used as reported.

13. For grains, only data on the sum of T-2 and HT-2, which were analytically determined in samples, were considered in the exposure assessment to allow for a direct comparison with the group HBGV (which is for the sum of both mycotoxins). For RTE products all reported values were considered, including individual T-2 or HT-2 occurrence data, due to the limited data available.

Seasonal variability

14. The presence of T-2 and HT-2 in crops is dependent on the weather at key growth stages, such as flowering, and can demonstrate large annual variability. While there are good agricultural practices deployed to manage the presence of mycotoxins in general, they have not proven to be effective for T-2 and HT-2, given the large dependence on climate/weather. Currently, liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) are the primary techniques employed for testing T-2 and HT-2 contamination levels in the laboratory. Commercially available rapid diagnostics kits delivering the simultaneous measurement of T-2 and HT-2 toxins, and most of the other tests available are immunochemical methods including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), lateral flow devices (LFDs)/dipstick assays and fluorescence polarisation immunoassays (FPIA) (Safefood, 2024). However, recent assessments by industry report large variability between the methods developed, and performance characteristics such as limits of detection (LODs) and, limits of quantification (LOQs) are often lacking (Safefood, 2024). This makes it difficult to reliably detect these toxins in samples. In addition, currently available test kits would not automatically be ‘fit for purpose’ (Safefood, 2024) as rapid tests must be accurate, reproducible and provide the required sensitivity for regulatory compliance.

15. The data from the call for evidence covers the years 2004-2024, which spans a period either side of the Commission Recommendation 2013/165/EU from 2013 on the presence of T-2 and HT-2 toxin in cereals and cereal products. Generally, the highest average levels of the sum of T2 and HT-2 received via the data call were reported in the years 2008 to 2014, with lower levels being detected thereafter. The year 2014 is still recognised as a year with a particularly high prevalence of T-2 and HT-2. A study by Xu et al. (2014) showed that in the UK, accumulation of T-2 and HT-2 mycotoxins in field oat grains was positively correlated with warm and wet conditions during early May and dry conditions thereafter, when toxin levels likely remained high because dry weather reduced their leaching or loss from the plant. As the occurrence of T-2 and HT-2 can be attributed to seasonal variation, reviewing levels across a longer period of time is particularly important.

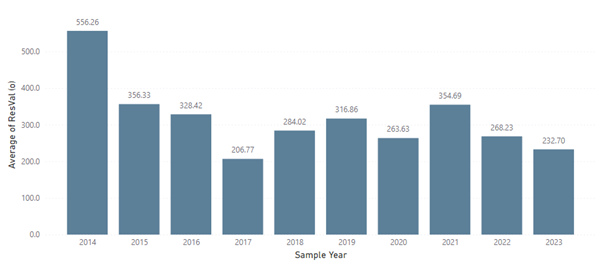

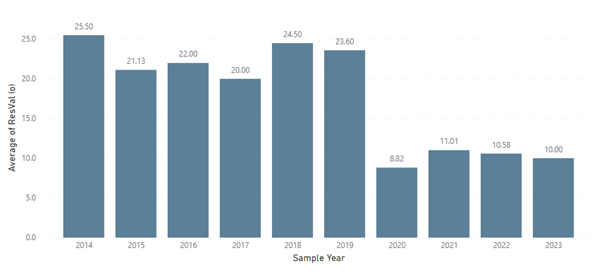

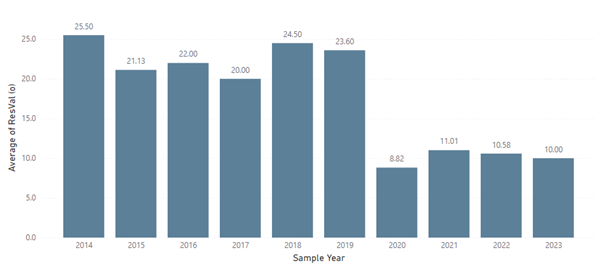

16. Figures 2a-c provide a visualisation of the annual occurrence data for the sum of T-2 and HT-2 in three cereal grains (oats, barley, and wheat), for unprocessed grain submitted via the call for evidence. The average values in these graphs are the median values per year. To get a more representative analysis of current exposure patterns, only the last 10 years of occurrence data were included (2014- 2024); the occurrence data from before 2013, the year the initial food safety Recommendation came into force, were excluded.

Number of samples: 2014 (n = 440), 2015 (n = 617), 2016 (n = 244), 2017 (n = 397), 2018 (n = 367), 2019 (n = 604), 2020 (n = 727), 2021 (n = 480), 2022 (n = 634), 2023 (n = 195).

Figure 2a. Average sum of T-2 and HT-2 concentration per year for unprocessed oat grains.

Number of samples: 2017 (n = 6), 2018 (n = 21), 2019 (n = 6), 2021 (n = 123), 2022 (n = 123), 2023 (n = 65).

Figure 2b. Median of T-2 and HT-2 concentration per year for unprocessed barley grains.

*ResVal(o) – concentration in µg/kg.

*ResVal(o) – concentration in µg/kg.

Number of samples: 2014 (n = 4), 2015 (n = 8), 2016 (n = 8), 2017 (n = 1), 2018 (n = 6), 2019 (n = 5), 2020 (n = 11), 2021 (n = 168), 2022 (n = 163), 2023 (n = 28).

Figure 2c. Average sum of T-2 and HT-2 concentration per year for unprocessed wheat grains.

17. It is important to note that the Figures are purely a visualisation of how the measured levels of mycotoxins changed across the different years. The level of information provided by industry in response to the call for data varied greatly, hence no one factor which was driving the changes observed in the mycotoxin levels across the different years could be identified. The annual variability depicted in Figures 2a-c could be based on factors such as i) climate, i.e. changes in the weather from one year to the next, ii) sampling time and storage, from time of harvest to time of measuring its mycotoxin levels, as well as the way and length the samples were stored and iii) increase in sampling.

Reduction factors for unprocessed cereal grains

18. Unprocessed oat grains intended for human consumption comprise of an outer hull which is the part of the grain that is often most contaminated. However, this outer hull is removed during processing, and this so-called ‘de-hulling’ process therefore significantly reduces the level of contamination.

19. A literature search was conducted to identify information on the reduction of T-2 and HT-2 mycotoxin levels in cereal grains during processing. A ‘reduction factor’, when used in exposure calculations, takes into account the expected decrease in T-2 and HT-2 levels in unprocessed cereal grains once they are processed, i.e. cleaned and de-hulled. Applying reduction factors would therefore allow for a more accurate representation of consumer exposure to T-2 and HT-2 and result in a more realistic exposure assessment. Several reduction factors for the sum of T-2 and HT-2 for oat grains were identified in the scientific literature ranging from 66 to 100 % (Meyer et al., 2022; Schwake-Anduschus et al., 2010; EFSA, 2011a; Pettersson 2008). For this assessment, a reduction factor of 85 % from Meyer et al. (2022) was applied; this means that all T-2 and HT-2 occurrence values for unprocessed oats were reduced by 85 %.

20. The factor of 85 % was chosen as it was the most scientifically robust as well as from the most recently conducted study. Although the reduction factor of 85 % was specifically for large oat kernels, Meyer et al. (2023) noted that “milling oats are traded to contain less than 10 % of thin oats below 2 mm slotted hole sieve” (up to 90 % of the oats may be composed of larger kernels). Therefore this reduction factor was considered to be of relevance for this exposure assessment.

21. As some cultivars of oat and barley are hulless, Polišenská et al. (2020) noted that “special attention should be paid to the risk of their contamination by Fusarium mycotoxins, as the rate of mycotoxin reduction during processing could be much lower than that for hulled cereals”. However, in the UK, hulless cultivars of oats are typically used for animal feed and not for human consumption.

22. No reduction factors were identified for maize or barley. The limited information available suggested that the starting levels and incidence of T-2 and HT-2 in wheat and maize were very low and hence limited data were available on their fate or how their levels changed during manufacturing of RTE food products (Scudamore, 2009). One publication by Pascale et al. (2011) calculated an overall reduction of T-2 and HT-2 toxins by 54 % following the processing of durum wheat. However, the samples used in this study were artificially inoculated with Fusarium, and as such the high concentrations of T-2 and HT-2 in this study were unlikely to reflect concentrations under natural conditions. Furthermore, the percentage reduction might not be linear and might be less at lower levels of contamination. Given the limited information it was therefore unclear whether, or to which percentage, processing reduces T-2 and HT-2 contamination in wheat, maize or barley under natural conditions.